How wonderful that we should invoke the most holy Trinity at the beginning of our talk on St Gregory of Nyssa, who was one of the greatest champions in the 4th century of this foundational dogma of our Christian faith.

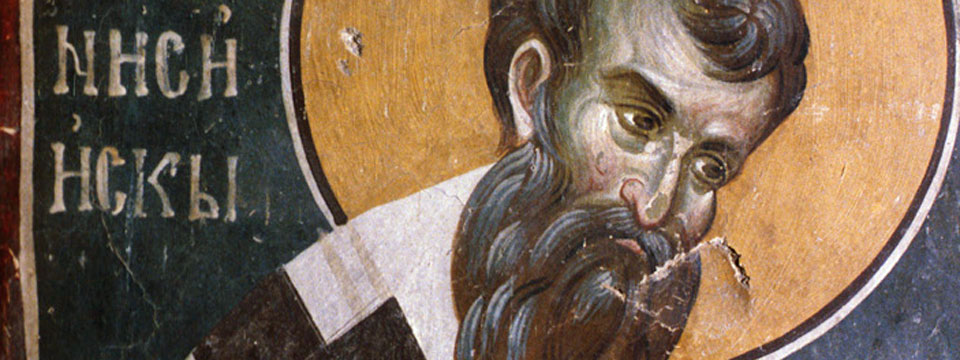

But first, the title of my talk: “Saint Gregory of Nyssa, Father of Christian Mysticism”. This is a mighty claim for any saint to have in his curriculum vitae, but I was most gratified to read that our Holy Father, Pope Benedict, has called him just that: “a father of mysticism”. Pope Benedict gave two catecheses on St Gregory during his General Audience on 29 August and 5 September 2007. In fact, he gave a long series of catecheses on the Fathers of the Church throughout this year, including St Basil and St Gregory the Theologian. As an aspirational scholar of St Gregory, I was pleased to see that most of what Pope Benedict had to say was up to date in terms of Patristic studies, and not a mere rehearsal of stale pious phrases. But of course you would expect this of Joseph Ratzinger, whose masterly and beautiful theology is so deeply rooted in the Liturgy and the Fathers of the Church. In calling St Gregory a father of mysticism the Holy Father is confirming and adapting a statement made by Jean Daniélou, later Cardinal, in his doctrinal thesis at the Institut Catholique in Paris in the 1940s. There Daniélou called Gregory not less than “the founder of Mystical Theology” in the Church.{{1}} Origen of course was too early, his theology too speculative, and his name subject later to too much controversy to bear this title. Our saint has received other high epithets in the history of the church. He was called the “Father of the Fathers” by Epiphanius the Deacon at the 7th ecumenical council on holy icons, Nicaea II (787), and “The shining light of Nyssa” by Nicephorus Callistus, a renowned theologian of the liturgy in the 13th century.{{2}}

Gregory, however, has not always been so appreciated. I recall reading an account of him in the Catholic Encyclopedia from about a century ago that damns him with faint praise as it were, associating him with the fringes of orthodoxy bordering on dangerous territory. This judgment of course has much to do with the Thomistic, scholastic and manualist mind-set that came to dominate the theological culture of the western church in the Tridentine era. Yes, Gregory was certainly a Christian Platonist, to the extent it is legitimate to use such a term, along with most of the Greek Fathers, and such orthodox luminaries of the Church in the West from St Augustine of Hippo onward. While his fellow Cappadocian Fathers received translation into Latin very early, translations of St Gregory of Nyssa percolated through to the West much more slowly, at the rate of many centuries, beginning I am pleased to say with the “Romanian” Church Father, Dionysius Exiguus, early in the early 6th century. Beginning with the first efforts to publish his works comprehensively in the 17th century, and fostered in the 20th century by such scholars as Jean Daniélou at the Institut Catholic in Paris and Werner Jaeger at Harvard during the 1940s and 1950s, such has been Gregory’s growing reputation in recent centuries that today no other Father of the Church is attracting more scholarly and spiritual attention than St Gregory of Nyssa.

The Christian Platonism of the Fathers

Before going on with St Gregory himself, I feel constrained to pluck up my courage and say something about the Christian Platonism of the Fathers. The important Philosophic schools in Antiquity as you know were Pythagoreanism, Platonism, Aristotelianism, Cynicism, Epicureanism, Stoicism and Neoplatonism. As far as their bearing on the development of Christian thinking goes, Cynicism and Epicureanism can be ruled out from the start. Though Aristotle was known and used by the Church Fathers, especially for his contributions to formal logic, the Stagirite as he was called found only limited favour at this period. He tended to be suspect since he was used so enthusiastically by heretics. Pythagoreanism was fairly subsumed into Platonic tradition. So that leaves us essentially just two significant players in the philosophic field during the early Church: Platonism and Stoicism.

Plato in a paragraph. How can I encapsulate Plato in one or two paragraphs? I shall try to steer close to concerns relevant to our topic. Plato who, interestingly, chose a life of celibacy the better to pursue philosophy, began by repudiating strongly the relativism, amorality and opportunism of Sophists of the 5th century BC. He stood for the objectivity of truth and the necessary link between living a virtuous life and seeking the truth. His philosophy has been described as “transcendental realism”, for to him, the realm of absolute truth is more real than this phenomenal, sensible world, which has only a kind of limited, partial reality. The dynamic aspect of the philosophic project can be called anagogy; that is, all our dealings with the phenomenal world are meant to lead us onward and upward to participation in ultimate realities. Thus Plato, at least in the earlier part of his course, invoked a theory of “forms”, that is, the principles of qualities such as beauty or the virtues – principles which more or less informed this lower realm. He would say, for example, that a flower “can only be beautiful insofar as it partakes of absolute beauty” (Phaedo 102B). The form of all forms was the Good, the One, which was considered to be ajkivnhtoi, unmoved, ajmetavstatoi, unchangeable, ajpavqhi, impassible or not subject to passion, suffering or being determined by any alien source, ajgenhv”, “uncreated” and “not subject to becoming” all of which terms became commonly acknowledged as divine attributes in Christian discourse. The last term especially, was going to be enormously disputed in the Arian crisis of the 4th century AD.

True human progress was in the liberation of one’s soul in the approach to this absolute realm, which was described in terms of participation or imitation of its qualities. One of the most famous analogies expressing this progress is that of the cave in the Republic (Rep 509E–511).

The intelligible and the sensible. Plato’s doctrine, in general, is marked by a sharp dualism between the noetic or intelligible on the one hand, and the sensible on the other, between the higher rational soul and the body. But where this was corrected by and yoked to Christian incarnationalism and sacramentality – and indeed by the Cross of our Lord Jesus Christ – it had the effect of fostering in Christian spirituality a certain élan, a dynamic, and, indeed, to use my old term, anagogical quality. At its worst it had a hyper-spiritualising and over-intellectualising effect. When Platonism was not tempered by Christian doctrine, it could feed heretical tendencies. Thus as we saw in my first talk published in the November 2009 issue of The Priest, the Arianism that racked the Church in the 4th century can be seen to a large extent as an recalibration of the Trinity in the terms of Neoplatonist emanationism.

With regard to Plato, I cannot forbear telling you one of my favourite stories from the Desert Fathers. There was once a desert father who in the privacy of his cell used to berate the pagan philosophers and curse Plato in particular, until one day Plato appeared to the monk and said to him: “Cease cursing me, man! For you must know that when the Lord appeared in Hades I was among the first to go forward to meet him.”

The anagogical and the sacramental. The anagogical character of Platonic discourse recommended itself to the sacramental/liturgical sensibility of the early Church and found a place in the discourse of many of the Fathers. It dovetailed well with the Christian economy of salvation, understood as a incarnationally mediated Divine Revelation, participation in which transforms us human beings and leads us onward and upward to sublime realities, even to union with God. This incarnational/symbolic/ participative approach, as it has been called, governed the way the Church of the Fathers engaged with Scripture and the sacred mysteries of the Liturgy. Our inward spiritual senses, retarded by sin, are to be re-awakened by these mediated forms of revelation, refined by our moral efforts in response to grace, and led upward to the highest intuition of the divine allowed to us in our human creaturely state: “contemplative union” in Western terms, theiosis in the terms of the later Greek fathers.

The whole manner of Divine Revelation is characterised by anagogy, that pedagogical method of the Spirit of God who through the course of sacred history endeavours always to lead man onward and upward. You can see this character of anagogy in an especially concentrated form in our Lord’s words and actions in the Gospel of John. Invariably our Lord intimates, reveals and calls us to a higher plane, to spirit and truth. Nothing is left to subsist on the lower plane. All points onwards and upwards. But lest we end up with a disembodied gnosticism, a deracinated “higher spirituality”, so to speak, it is also an essential feature of this most spiritual of the Gospels never to lose its purchase of the concrete, to be ever returning to the earthly, the material, the tangible and the physical and re-investing it with significances acquired from on high. One could describe this dynamic as a constant “circumincession” between the earthly and the heavenly realms, the inter-manifestation of flesh and spirit, one in the other: “on earth as it is in heaven”.

Upward, Godward direction. All aspects of the life in Christ, the incarnational, liturgical, ecclesial, doctrinal, moral and pastoral, together with the loftiest spiritual and mystical aspirations of prayer all conspire together to lead us in an upward, Godward direction, to sublime communion with the most holy Trinity. Whatever else transpires in the intellectual life of the Church down the centuries, this sapiential or contemplative manner of the Gospel of John, this always pressing on to ultimate significances, is the core of its core, and we should remember that, and keep coming back to it and immersing ourselves in it, endeavouring to form our sensibilities by it. By “sapiential”, I mean “savouring in such a way that leads to wisdom”, and “wisdom” we might describe as the mutual penetration of knowledge and love.

Rationalism in contrast to symbolic, symphonic. The Christian Aristotelianism of the 13th century dealt creatively with the challenge of contemporary forms of Aristotelianism, and, after suffering a bit of an eclipse in late medieval times, was eventually very successful in the post-Tridentine Church in the West for various reasons. It introduced however a culture of the mind very different to that of the sacred liturgy and of the Fathers: a mindset habituated to, and fixated upon analysis (that is, of breaking things apart to see what they are made of, and a tendency to leave them there in their discrete compartments). What I am criticising here is not so much the content of scholastic argumentation, but the lasting disposition of mind which it seems to breed in men of much less calibre that St Thomas Aquinas. Rigorous intellectual enquiry has great importance, and the Church Fathers were masters of it, but having employed it, tended always to resolve their discourse in the symbolic, symphonic spirit of triniatarian doxology, of the sacred liturgy. Their motivation and their orientation was wholly theocentric. Scholasticism delighted in neatly delimited categories, notably between the natural and the supernatural, between grace and nature, etc. all of which continued more or less a tendency to be found in the natural philosophy of Aristotle himself. The 17th century in particular seems to have been a bad century for losing the ancient spirit of the Church and the Fathers of forgetting the mystical synergy between outer and inner that was supposed to be exemplified above all in the sacred liturgy.

I had a few delightful exchanges with the Archbishop of Granada, Xavier Martinez, last year, at the quadrennial international Symposium Syriacum. He had devoted special study to the Fathers of the Church in his youth and had even studied Syriac, and hence, hosted the Conference in his diocese that year. Vitally interested in what is really needed for the true renewal of the Church, he thinks for one thing the Church in western needs to be re-irrigated by the Fathers of the Church and by the liturgical traditions of the Eastern churches. On the one hand he has to shepherd an emotional Baroque-era pietism, administered by priests and orders of a scholastic bent. In his heart of hearts, however, he does not think this is the answer to the rejuvenation of the Church in the West, but part of the problem. Then there are other extremes in the Church in Spain. He muttered darkly about Jesuits one day to me. He has had huge battles with Rahnerian Jesuits in the field of theological education in his diocese, and in fact, to great controversy, withdrew all his students for the priesthood from their theological supervision. He said to me one day, “You know, Anna, Suarez began here, in this city!”

Suarez is the classic hyper-Scholastic, a brilliant and indeed devout Jesuit who lived in the early 17th century. Later the Archbishop informed me in tones of sorrow: “Do you know he taught that natural man has no need of Christ?” That staggered me. If Suarez really taught that, it can only be a symptom of the hyper-compartmentalised world of the scholastic mind-set, and in a weird way, frighteningly prophetic of what has come about in the West today. Such a conception would be unthinkable to the Fathers of the Church, and above all to St Gregory of Nyssa, to whom Christology was profoundly bound up with Trinitarian Theology on the one hand and Anthropology on the other. I have listened to Tracey Rowland, a great doxographer of the intellectual trends current at the time of Vatican II. She has argued that paradoxically it was some of the over-easy dichotomies of a certain type of Thomistic thinking that actually lent a handle to the triumph of secularism in the Church as a supposed means of renewal. Even Pope Paul VI spoke of liturgical reform as a matter of separating out the essence from the form in which it is presented, and re-expressing it for our time. This way of thinking involves supposing a divorce between form and content much along the lines of the accidents and the res of the medieval schoolmen. The results for the Church in my opinion have been catastrophic.

Mystical presence of Christ. Just in this past week or two, I have read Pope Benedict’s catechesis of a great theologian of the Carolingian era: John Scotus Erigena. He was rare among Western theologians in being erudite in both Greek and Latin. He was steeped in St Gregory of Nyssa, translating into Latin Gregory’s On the Making of Man, a challenging highly intellectual work. I know this very well, since I myself have translated it. He also translated Pseudo-Dionysius’ works Mystical Theology and On the Divine Names, which became known to the great medieval theologians through his translations. And what increases my respect for him, he was an assiduous student of St Maximus the Confessor, that most awe-inspiring and profound exponent of Christology, who brought to an end centuries of ferment on Christological issues. Thinking the other night in bed, it dawned on me the sequence of influence that runs all the way from St John of the Cross, who in speaking of contemplation as “a ray of darkness”, is quoting Pseudo-Dionysius,{{3}} and is hence dependent on Erigena’s translation, and, on Pseudo-Dionysius’ master, St Gregory of Nyssa.

So Erigena knew the Greek Fathers, and especially their doctrine of theosis, in which the profoundest treatment of Trinitarian theology, Christology and anthropology converge in an account of the ultimate destiny of man. Alas, this was not understood or well received in the West, and he was relegated for what were supposed to be tendencies to pantheism. Yes, he was certainly a Christian Platonist.

All of this is covered in Pope Benedict’s catechesis. Yet Erigena elicits the Holy Father’s renewed esteem, who says of him, “And yet the enchantment and that aura of authentic mystical experience, which every now and then one can feel tangibly in his texts, endures.” But the point I want to make is to compare him with Suarez above. If the end of Christian Aristotelianism can bring you to believe that natural man has no need of Christ, behold what dangers Christian Platonism can bring you to, when, as Pope Benedict quotes him, Erigena says:

We should desire nothing other than the joy of the truth that is Christ, avoid nothing other than his absence. The greatest torment of a rational creature consists in the privation or absence of Christ. Indeed this must be considered the one cause of total and eternal sorrow. Take Christ from me and I am left with no good thing nor will anything terrify me so much as his absence. The greatest torments of a rational creature are the privation and absence of him.”{{4}}

Marvellous! How absolutely marvellous! And what a perfect antidote to Suarez! Thank you for such a liberating word, dear Lord.

Gregory’s family

But now let us return to the person of Gregory. As you know, he is one of the so-called Cappadocian Fathers, who include St Basil the Great, his brother, their friend, St Gregory the Theologian, also called Nazianzen, and the latter’s nephew St Amphilochius of Iconium. In my earlier paper on the turmoil of the Church in 4th century outlined how Arianism was the attempt to reconfigure the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit of Matthew 28:19 to a sophisticated NeoPlatonist emanationism. At stake was Christian identity: was the Church’s faith and doctrine wholly conformable to the latest and best in philosophical thinking, or was there an element in it inalienably deriving from other sources and irreducible to the spirit of the times? The Cappadocian Fathers lead the struggle for Christian orthodoxy in the final phase. The two Gregorys, Gregory Nazianzus and Gregory of Nyssa brought Basil’s work to a crowning completion in the council of Constantinople in 381,{{5}} when the Christian doctrine of the Trinity was re-affirmed and the divine nature of the Holy Spirit was defined.

Before we look further into Gregory’s distinguished role in the history of Christian spirituality, we should first understand him in the context of his family. Gregory of Nyssa was a scion of what I will quite plainly declare the most remarkable family in Christian history. His parents, Sts Basil senior of Pontos and Emmelia of Cappadocia, were already the heirs of martyrs and confessors of the faith, including St Macrina the Elder, Basil senior’s mother, whom we might well call “shining light of the Church in Neocaesarea”, after her hero, St Gregory the Wonder-Worker. Incidentally, Gregory of Nyssa wrote the earliest and greatest biography of that saint, which includes the first known account of an apparition of Our Lady, which in turn reminds us that Gregory of Nyssa also deserves notice for his incipient Mariology, but we do not have time to go into that, except to point out that he, though generally an early exponent of Antiochene Christology, certainly called Mary by the Alexandrian title Theotokos, or God-bearer. Turning to the mother, Emelia’s grandfather had died a martyr in the Decian persecutions. Such were the Christian antecedents of this holy married couple, who were themselves accorded the cult of sainthood and have feast days in the Greek Church. Truly, if the faithful today deserve inspiring examples of married holiness, Sts Basil and Emmelia are prime candidates for wider exposure. They should be in the universal calendar of the Western church, and if, by God’s grace, I visit the Vatican Library next year, I might make a visit to the Congregation of Causes of the Saints and attempt to remind them of it.

But when we turn to Basil and Emmelia’s ten children, the Christian impulse, already strong, picks up even further swell. Four if not five were destined to recognition as saints, and great saints at that: the first-born, St Macrina the Younger, who led her whole family in zeal for the virginal and ascetic life, whom I call the Mother of Greek Monasticism, and her four holy brothers, three of them bishops, two of them renowned Fathers of the Church: Saints Basil of Caesarea, called “the Great” and the “shining light of the whole world,”{{6}} the third son, St Gregory of Nyssa, and the youngest born, St Peter of Sebasteia, himself a monastic father, whom Gregory repeatedly calls “the great Peter”.{{7}}

The second son, Naucratius, was in fact the first to follow his sister’s example in renouncing the world for the ascetic life, but he died tragically in an accident at age 26. He has I think, historically received some cult of sainthood. Remarkably I have been privileged to stand at the very spot where the accident happened. Another daughter of the family, Theosebia, isthe subject of glowing praise by St Gregory the Theologian as a great model and leader among Christian women. I have little doubt that many Christian families over the centuries could roll out some holy parents and holy children, but where else, I ask you, are you going to find such a galaxy of holy forbears and holy siblings of such high calibre?

Gregory, husband and father. You may be surprised to learn that spiritually this future Father of Christian Mysticism, our Gregory, was spiritually the slowest off the mark of all his known siblings, but catch up he did, in real earnest, which should give us laggards and desperadoes some hope. Though initially participating in the ascetic experiments of his sister Macrina and his brother Basil, he quit it all in the year 364, and chose a secular career in the world. He became a rhetorician instead, something like a university professor of classics and humanities today. It was his season of youthful refusal. Later he deeply regretted his decisions at this period of his life. He married, that is for certain. In my book, St Gregory of Nyssa: the Letters, I investigate his marital status and come to the conclusion that he probably married in about 364/365, that he may have had a son, Cynegius, and that it seems likely that his wife died at her first confinement. He was at any rate a widower by the time he wrote his first work at Basil’s behest, in about the year 371. It was called On Virginity, which offers many fascinating clues, simmering just below the surface, of what he had been through in the previous few years, especially the unexpected death of his wife, and the sudden, immensely painful loss of that promise of earthy happiness that was marriage. Gregory’s On Virginity reflects the teaching and example of his sister Macrina, whom in letter 19 he calls “his teacher”, and “a mother in place of our mother”. By now (that is, the year 370/371), Gregory was fully attuned to the noble ideals lived by his sisters and his brothers Basil and Peter.

Gregory, bishop. If you take the point of view of the “Hound of Heaven”, the Lord had certainly been in dogged pursuit of his slow-to-learn servant Gregory. Caught in a kind of spiritual pincer movement between the likes of Macrina, Theosebia and Peter up in Pontus, and Basil and Gregory Nazianzen down in Cappadocia, and given his own extraordinary gifts, the Lord did not leave his Gregory to paddle in the spiritual shallows. There he was, a teacher of the higher curriculum in the city of Caesarea in the year 370, when his brother was elected metropolitan archbishop of the same city. It took Basil some little while, but eventually he succeeded in winning his brother’s rich gifts for service to the Church. Late in 371 Basil co-ordained his brother as a priest and a bishop to serve in Nyssa, a town in the far west of his ecclesiastical province towards Galatia, about three days journey from Caesarea. With my sister Carmel, I visited the site in 2006.

We need not go into the Gregory’s scantily recorded activity in the early to mid-370s, how he was extruded from his see by imperially backed Arianizers as a way of getting at Basil, of how he returned in the summer of 378 after an amnesty granted to Neo-nicenes by the Arian emperor Valens shortly before his fatal war with the Goths. Suffice it to say that when Gregory did at last return home, he found his great brother Basil in his dying weeks and days. St Basil the Great died in late September of 378 at the age of only 48 or 49years. Gregory was by his bedside. To him the dying Basil solemnly entrusted the baton of defending true doctrine. Shortly afterward, in his earliest surviving works from this period, Gregory begins to express himself very consciously as Basil’s successor and continuator as an expositor of the Christian faith.

The next year, in May 379, Gregory attended the council of Neo-nicenes in Antioch. He had scarcely returned to Cappadocia, when he got wind that his sister Macrina was gravely ill. He sped up to Pontus as quickly as he could and reached it by an amazing providence the day before she died, on 22 July, 379. Gregory tells of the events surrounding her deathbed in one of the greatest jewels of Christian biography, The Life of Macrina, in which he presents his sister as the perfect Christian philosopher, the teacher of virginity and the life of whole-hearted cleaving to God.

Gregory as a Catholic Father of the Church

Though I am always one to champion a greater consciousness of the Greek Fathers, and of the Eastern Churches in the West, it is worth adverting to the fact that Gregory was very much a Catholic Father of the Church. The fact that he is a Greek Father and not a Latin, does not mean that the Eastern Orthodox as they later historically developed, have an unalloyed right of franchise over him. This is an intriguing topic, but I offer you three instances where his doctrine contrasts with positions later adopted by the Greek and Slavic churches. Apart from the obvious fact that he and all the Cappadocian Fathers lived in ecclesiastical communion with the Pope of Rome and indeed sought it, Gregory makes a point in his Letter 17, that the Christian status of the church of Rome in no way depended on its civil dignity, but on the purely Christian credentials of the humble fisherman, the apostle Peter. Basically Gregory is saying that the importance of Rome in the Christian scheme of things is its connection with Peter, not with the Roman emperor. He states this in the 380s as matter of fact and obvious, and yet it flatly contradicts the line taken by the Constantinopolitan tradition as early as the following century, at the council of Chalcedon. Secondly, he is definitely one of the Greek fathers you could cite to support a theology of the procession of the Holy Spirit from the Father and or with the Son. In the sharp dichotomies much put forward by later Orthodox theologians over the matter of the filioque, they have their work cut out trying to demonstrate that Gregory is one of theirs. Thirdly, though Gregory if anyone is going to stress the freedom that is intrinsic to the dignity of the human being as created by God, he has also, paradoxically, a very strong sense of the Fall and its legacy of moral damage to the whole human race, surprisingly close to, though not using quite the same terms as, the Augustinian theology of original sin as later ratified in the Western theological tradition.

The Council of 381 appointed Gregory together with two other prelates as living pillars of orthodoxy for the region of eastern Asia Minor. To be in communion with them was a litmus test of doctrinal orthodoxy. Gregory really came into his own in the early 380s as a kind of consulting theologian of the eastern Roman empire. Let me stress here his awesome intellectual capacities. Through his writings in the 380s Gregory became the greatest speculative theologian among the Greek Fathers between Origen in the 3rd century and St Maximus the Confessor in the 7th century. He wrote many works of primary Catechesis, and on a more sophisticated level, treatises and doctrinal letters on Anthropology, Christology, Eschatology and Trinitarian theology. Through all of these, attention to Holy Scripture runs like a common thread, as well as a supple and intense use of reason and argument. Emperor Theodosius called on him as panegyrist of the imperial family several times. It would be fascinating to show how Gregory was by no means as gifted as his brother Basil as a church administrator and politician, even though he surpassed him as a speculative theologian. Gregory never lost a certain naivety, and knew real failures in dealing with people. It endears him to us. It would also be interesting to discuss the personality traits revealed in his letters and his writings, but I must refer you to my book on that, if you wish to pursue it further (see fn 9). Towards the end of the 380s, as the emperor Theodosius moved to Milan, and as more and more of his family and friends were dying, and he himself was aging, Gregory’s thoughts and his writings turned to one topic alone: mystical theology. He devoted his great gifts as a speculative theologian to expounding the primordial human vocation to union with God and what happens to us if we set out to answer that call in real earnest.

Building blocks of Gregory’s thought

In Gregory’s thought, if we are to understand man’s vocation to divine union, we must begin with anthropology; that is, the question of just what man was originally constituted by the Creator to be. Of course that assumes a stance of theistic creationism, and relies on revelation. Given that context then, what man is, intrinsically, shows clearly his end or ultimate destiny. Of course, a correct Christian anthropology has a great bearing on one’s understanding of how the divine Logos became incarnate – that is, on Christology, an extremely important topic, since for Gregory the Person of Christ is above all the Image of God made manifest.

Man: imago dei. The anthropological truth, or as John Paul II would put it, the truth about man that governs all Gregory’s ascetical theology is that man is created in the image and likeness of God. Man was and is ordained to divine likeness. Both the Fall and personal sin have severely compromised that pristine vocation, so that the journey of recovering our likeness to God that is set before us requires moral toil, that is, contending against disordered passion or vice, which – positively stated – is the diligent cultivation of virtue. The divine nature is revealed to us in Christ who is the Image of God incarnate, the prototype to whom we must tend. An excellent passage that unites Gregory’s christological and ascetic teaching is found in his brief treatise On Christian Perfection:

What then ought that man do to be deemed worthy of the great name of Christ? What else except to examine carefully in himself his own thoughts and words and deeds, to see whether they one and all tend towards Christ or are foreign to him. To make such an examination is very easy. Any action, thought or word which involves passion is out of harmony with Christ and bears the mark of the adversary, who smears the pearl of the soul with the mud of the passions and dims the lustre of that precious jewel. Anyone pure of every inclination of passion tends towards the source of freedom from passion, namely Christ. If a man draws from Him his thoughts, as though drawing from a spring that is pure and unsullied, he will reveal in himself the same likeness to his prototype as there is between two kinds of water, that which is in a running stream and that which is drawn from the spring in a jar. Purity has only one nature, both that which is in Christ and that which is seen in the one who has a share in Him: Christ is like the spring which gushes forth, the one who shares in Christ draws from Him, as it were, and brings beauty of thought to his life. And so there is a harmony between the hidden inner man and the outer man when decency of life is joined with thoughts which are moved in accord with Christ.

Man: his theiosis. The work of assimilation to the divine nature through virtue requires that we turn trustingly, constantly and perseveringly to God in prayer. In the first of Gregory’s sermons on the Our Father, Gregory powerfully exhorts to the necessity of prayer, if we are to find the strength to contend with vice and make progress on the journey to perfection. Gregory cries out to us:

Anyone who does not unite himself to God through prayer is separated from God. Therefore we must learn first of all that we ought always to pray and not grow weary (Lk 18:1). For the effect of prayer is to join us to God, and anyone who is with God is far from the adversary. Through prayer we strengthen and safeguard our charity, bridle our anger, and subdue and control our pride. Prayer leads us to forget our injuries, vanquishes envy, disarms injustice and makes amends for sin. Through prayer we obtain physical well-being, a happy home, and a strong, well-ordered society. It is prayer that will make our nation powerful, give us victory in war and security in peace; it reconciles enemies and preserves allies [think about it, the forgotten importance of prayer in politics and international relations!]. Prayer is the safeguarding of virginity, and the guarantee of fidelity in marriage, the shield of the traveller, the protection of the sleeper, and the encouragement of those who keep vigil…. Prayer is intimacy with God and contemplation of the unseen. It answers our yearnings and makes us the equal of angels. Through prayer the good is fostered, evil destroyed and sinners converted.{{8}}

And the last word: Gregory, man of prayer. But what of Gregory himself at prayer? Let us look at an autobiographical passage from his Letter 18 to Otreius of Melitene. Early in the year 380 Gregory found himself after a terrible year, held captive in Sebasteia – we need not go into the details here. In his letter he looks back longingly at the home he is deprived of, lamenting his:

dearly loved home, brothers, relatives, familiars, associates, friends, hearth, table, store-room, pallet, the bench, the sacking, the secluded corner, the prayer, the tears – how sweet they are, and how dearly prized through long habit, I need not write to you who know full well.{{9}}

It may not be much, but from 1700 years perspective this is a precious little glimpse of Gregory in a secluded corner of his house at prayer, and making a long habit of it.

There is another passage from his letters we should look at. It comes at the end of his Letter 6, and it shows Gregory returning to his church at Nyssa after a long exile:

When we had come within the portico, we saw{{10}} a stream of fire coursing into the church, for the choir of virgins{{11}} was processing in line into the entrance of the church carrying tapers of wax in their hands, kindling the whole to a splendour with their blaze. And when I had entered and had both rejoiced and wept with the people – for I experienced both these from witnessing both passions in the crowd – as soon as I had finished the prayers, I wrote out this letter to your holiness as quickly as possible….{{12}}

Here again we have a precious glimpse of Gregory, as bishop and chief liturgist of his church, leading his people in the great prayer of Christ the High Priest, the divine liturgy.

[[1]]J. Daniélou, Platonisme et théologie mystique: Essai sur la doctrine spirituelle de saint Grégoire de Nysse (Paris: Aubier, 1944), 6.[[1]]

[[2]]There are other glowing epithets: He was called oJ tw`n Patevrwn Pathvr (“the Father of the Fathers”) by Epiphanius the Deacon at the 7th ecumenical council, Nicaea II (787), 6th session (Mansi XIII 203-364 at 293E / Labbé and Cossart, Concilia vol. VII, 477), and oJ tw`n Nussaevwn fwsthvr (“the shining light of Nyssa”), Nicephorus Callistus H.E. xi. 19.[[2]]

[[3]]Ascent II.8.6, referring to Pseudo-Dionysius, Mystical Theology 1.1 (1000A). The same passage from Pseudo-Dionysius is again mentioned by John of the Cross in Spiritual Canticle 14.16. Cf. also Spiritual Canticle 39.12, where the “knowing by unknowing” brings to mind the negative theology of Pseudo-Dionysius, for instance: “…the most divine knowledge of God, that which comes through unknowing, is achieved in a union far beyond mind, when mind turns away from all things, even from itself, and when it is made one with the dazzling rays, being then and there enlightened by the inscrutable depth of Wisdom” (PseudoDionysius, Divine Names 7.3 (872A–B). I am indebted to my friend Anthony Nott for these references.[[3]]

[[4]] Quoted from Erigena’s De Divisione naturae, by Pope Benedict XVI, in “Authority and Reason work as a pair”, L’Osservatore Romano Weekly Edition in English, Forty-second year, number 24 (2009), Wednesday 17 June 2009, p. 11.[[4]]

[[5]] It commenced with Basil’s friend, Gregory of Nazianzus, who was then the Bishop designate of Constantinople. He had been instrumental in rallying the Neo-Nicene orthodox in the imperial city. For a general survey of the Arian controversy culminating at this council, see H. Chadwick, The Early Church, rev. ed. (London: Penguin, 1993), 133–151, and J. Daniélou and H. Marrou, The Christian Centuries: The First Six Hundred Years (London: Darton Longman and Todd, 1964), 255–268. For a more detailed study of the later phase and the pivotal role of the Cappadocian Fathers, see Thomas A., Kopecek, A History of Neo-Arianism (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1979).[[5]]

[[6]]BasiJleio~ oJ mevga~, oJ th`~ oijkoumevnh~ fwsthvr, Theodoret H. E. 4.16; and in Theodoret Letter 146, oJ tw`n Kappadokw`n, ma`llon de; th`~ oijkoumevnh~ pwsthvr , “the shining light of the Cappadocians, or rather, of the whole world”.[[6]]

[[7]]VSM GNO 412, Callahan 189.[[7]]

[[8]]Homily 1 on the Lord’s Prayer, in St Gregory of Nyssa: the Lord’s Prayer, the Beatitudes, tr. and annot. Hilda C. Graef (Westminster Maryland: the Newman Press, 1954), p. 24.[[8]]

[[9]]Letter 18, A. Silvas, Gregory of Nyssa: the Letters (Leiden: Brill, 2007), 169–172 at 171.[[9]]

[[10]]OJrw`men in the mss., but translating according to sense, wJrw`men.[[10]]

[[11]]Compare the description of Gregory’s arrival at Annisa in VSM 18.3 (GNO 8.1.387–388 Maraval 192–194). The virgins came out in Gregory’s honour but awaited him at the entrance to the church.[[11]]

[[12]]Letter 6, A. Silvas, Gregory of Nyssa: the Letters (Leiden: Brill, 2007), 140–142 at 142.[[12]]