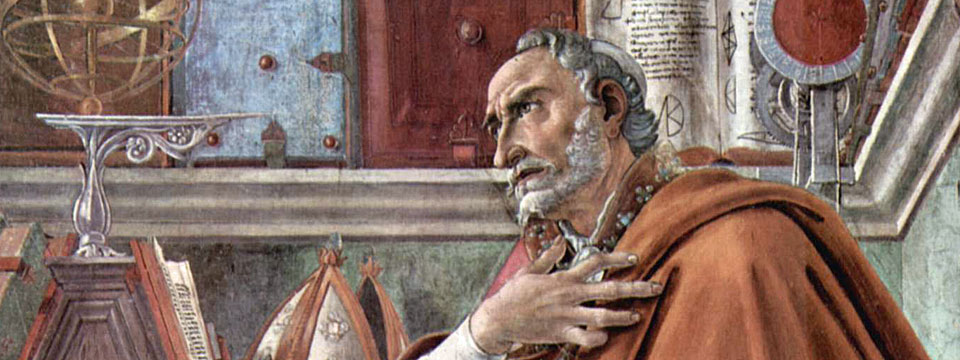

Cardinal Newman

John Henry Newman (1801 – 1890AD) was born and brought up an Anglican. He had some kind of conversion at the age of fifteen when he tells us that he received “impressions of dogma, which, through God’s mercy, have never been effaced or obscured”. From that time he lived a serious and devout life and went to Oxford University where eventually he was ordained as an Anglican Clergyman and gained great honours as a student then as a teacher and preacher.

Through the study of the Fathers of the Church, and another deep spiritual conversation whilst travelling around the Mediterranean, he drew closer and closer to Catholicism. He was one of the leading lights of the early Anglo-Catholic enterprise found especially in the Oxford movement. Eventually he realised, at great cost to himself, that the voice of history was pointing to the Catholic Church alone as ‘the one fold of the Redeemer’. He could no longer accept the Anglican middle way (via media) between Catholicism and Protestantism. He wrote:

For a mere sentence, the words of St Augustine, struck me with a power which I never had felt from any words before ….. they were like the ‘Tolle, lege, — Tolle, lege,’ of the child, which converted St Augustine himself. ‘Securus judicat orbis terrarum!’ (secure is the judgement of the whole world). By those great words of the ancient Father, interpreting and summing up the long and varied course of ecclesiastical history, the theology of the Via Media was absolutely pulverised (Apologia Pro Vita Sua, part 5).

In 1845 at the hands of Blessed Dominic Barberi (1792-1849AD) he was received into the Church at Littlemore. He went on to become a Catholic priest, he founded the Oratory of St Philip Neri in England and wrote some of the most important theology ever to come out of this land. He was not always understood or appreciated in the Church as he wrote in a peculiarly non-scholastic fashion. Eventually his genius was recognised and he was made Cardinal by Pope Leo XIII in 1879.

Newman is not always classed as an apologist and yet so many of his great works are written to address particular controversies of his time. The stated intention, for instance, in writing An Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine was to create ‘an hypothesis to account for a difficulty’. It was Newman who said that doctrine often develops because of heresy and in response to it. He could therefore have easily concluded that it was apologetics that was the major force behind the development of Christian doctrine.

His great University Sermons are principally apologetic works which teach us the true relationship between Faith and Reason. Newman’s Grammar of Assent gives us a deep understanding of the act of faith itself in response to accusations of loose reasoning in religion and emotionally driven belief.

His own life became an apology for the truth of the Catholic faith. He titled his story of conversion Apologia Pro Vita Sua. It was indeed a defence of the integrity of his journey to the Catholic faith and of his good name after various calumnies against him. The work reveals how he followed the light of truth often at the greatest cost to himself.

G. K. Chesterton

Gilbert Keith Chesterton (1874-1936AD) is widely acclaimed as one of the very greatest apologists. His contributions to journalism (especially in the Illustrated London News) and literature (most notably his Fr Brown detective stories and his poetry) are well acknowledged. However, his particular genius was in his defence of Christian faith and common sense philosophy and social teaching. When asked why he became a Catholic he responded, “To get rid of my sins”. He said, “The Catholic Church is the only thing which saves a man from the degrading slavery of being a child of his age.” And elsewhere, “To become a Catholic is not to leave off thinking, but to learn how to think.”

When he died on 14th June 1936 he was an acknowledged national hero and literary giant. His natural human goodness won him even the admiration of his adversaries. George Bernard Shaw described him after his death as “a man of colossal genius”.

Chesterton is perhaps most renowned for his humour as an apologist. He is a master of irony, sarcasm and indeed even slapstick presentations of human incongruities. He is called the ‘prince of paradox’. Here is one example that is often used from his The Man Who was Thursday:

Thieves respect property. They merely wish the property to become their property that they may more perfectly respect it.

Paradox in the relationship between the divine and the human was often brought to the fore and he allows us by these alternative visions to look at the world anew and marvel.

Another technique that Chesterton employed was exaggeration and hyperbole. He was capable of rousing emotions, just as Winston Churchill, one of his contemporaries, did in his political speeches of the time. His humanity also shines through and he was known after good-natured debates to have a pint with his adversaries (such as H. G. Wells and G. B. Shaw). This did not mean that he thought lightly of the subjects discussed but that human courtesy and charity had its own persuasive power and must never be sacrificed in the search for truth.

Here is a short quotation from Chesterton’s Orthodoxy (ch.6) which gives encouragement to every apologist:

This is the thrilling romance of Orthodoxy. People have fallen into a foolish habit of speaking of orthodoxy as something heavy, humdrum, and safe. There never was anything so perilous or so exciting as orthodoxy. The Church… swerved to left and right, so exactly as to avoid enormous obstacles. She left on one hand the huge bulk of Arianism, buttressed by all the worldly powers to make Christianity too worldly. The next instant she was swerving to avoid an orientalism, which would have made it too unworldly.

The orthodox Church never took the tame course or accepted the conventions; the orthodox Church was never respectable. It would have been easier to have accepted the earthly power of the Arians. It would have been easy, in the Calvinistic seventeenth century, to fall into the bottomless pit of predestination. It is easy to be a madman: it is easy to be a heretic. It is always easy to let the age have its head; the difficult thing is to keep one’s own. It is always easy to be a modernist [or a postmodernist]; as it is easy to be a snob.

To have fallen into any of those open traps of error and exaggeration which fashion after fashion and sect after sect set along the historic path of Christendom—that would indeed have been simple. It is always simple to fall; there are an infinity of angles at which one falls, only one at which one stands. To have fallen into any one of the fads from Gnosticism to Christian Science would indeed have been obvious and tame. But to have avoided them all has been one whirling adventure; and in my vision the heavenly chariot flies thundering through the ages, the dull heresies sprawling and prostrate, the wild truth reeling but erect.

Monsignor Knox

Ronald Knox (1888 -1957) was born an Anglican, son of Bishop Edmund Knox. He was educated at Eton and Oxford. He had a glittering career as a classicist winning several prizes and scholarships. He was made a fellow of Trinity College in 1910 and went on to become chaplain after Anglican ordination in 1912. In the midst of the First World War he was converted to Catholicism. Interestingly the account of his conversion is written in a book aptly called Apologia (1917). Another account is found in his A Spiritual Aeneid (1918).

After ordination as a Catholic priest in 1918 he became a seminary tutor at St Edmund’s Ware. His period of greatest reknown and literary output came between 1926-1939 when he was Catholic chaplain at Oxford. He was chosen to preach at the funeral of G. K. Chesterton. He established himself as a great preacher and writer. Some of Knox’s most famous works as an accomplished linguist are in fact translations. His editions of the Imitation of Christ and the Story of a Soul are very popular even today. He translated Jerome’s entire Latin Vulgate into a modern, homely, earthy, English style.

His apologetic material is found scattered throughout his writings, not least in his wonderful sermons. The book, first written for university students, The Belief of Catholics (1927) contains a great detail of superb apologetic writing. Sadly, whilst he was working on a more extensive work of apologetics in the 1950s he fell seriously ill and died of cancer in August 1957. Such was his popularity that the great novelist Evelyn Waugh wrote a biography of his life in 1959.

Waugh thought that Knox’s satire as demonstrated in Enthusiasm represented one of the greatest literary masterpieces of the 20th century. It was this spirit of satire, being able to mock the ridiculous, and show the eccentric for what it is, that also characterises Knox’s apologetics. It is always extremely balanced and sensible, never fanatical or exaggerated.

Knox continued the great tradition of Chesterton (his mentor) in the 1940s and 50s but with a distinct style and method of his own. He was an expert in detective literature and a writer in this genre himself. His apologetics often reads as a detective story, the uncovering of the hidden truth and the working out of a seemingly unsolvable riddle.

Perhaps Knox’s greatest gift is that he allows us to approach great and terrifying mysteries in a confident, yet humble, matter of fact way. His writings on the Mass in Slow Motion and the Creed in Slow Motion became overnight best sellers because of their simple straightforward clarity.