Pied Beauty

Glory be to God for dappled things —

For skies of couple-colour as a brinded cow;

For rose-moles all in stipple upon trout that swim;

Fresh-firecoal chestnut-falls; finches’ wings;

Landscape plotted and pieced — fold, fallow, and plough;

And áll trádes, their gear and tackle and trim.

All things counter, original, spare, strange;

Whatever is fickle, freckled (who knows how?)

With swift, slow; sweet, sour; adazzle, dim;

He fathers-forth whose beauty is past change:

Praise him.

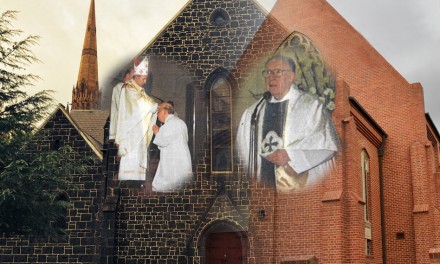

Fr Gregory Jordan SJ

1930-2015

Gerard Manley Hopkins could best describe his brother Jesuit, Gregory Fraser Jordan SJ as “counter, original, spare, strange” and in so doing he would allude to the beauty of a priest’s life and death that had an influence on the rich, the poor, the strong and the sick, the young and the old.

Fr Jordan would probably look askance if I described him as a “dappled thing” but no doubt he would have some witticism ready in response or perhaps go one better and begin to recite Lepanto. Gregory Jordan was not one to be upstaged and rarely without something worth saying.

In any event, he would appreciate the literary reference and the opportunity to unveil yet another jewel of Catholic culture that it might be beheld, enjoyed and understood by the faithful, especially the enquiring minds of the young. And in doing so, Fr. Jordan was “counter,” to the culture of the day; “original” in that he was one of the few priests with the ability to do this; “spare” in the Old English meaning of the word, that is to say “rare;” and “strange,” as things of rarified beauty always remain somewhat other-worldly in what appears to be a mundane existence — unless one is familiar with the God who transcends that existence and the Truth, Beauty and Goodness that flow through creation in His wake.

Print Friendly Format

Download and view this article as it appeared in the Summer 2015 issue of The Priest.

Son of Ignatius

On the fourth day of the Ignatian Spiritual Exercises, the Jesuit considers how Christ calls and wants all under His standard. A great field near Jerusalem is contemplated and there the supreme Commander-in-chief, Christ the Lord, commands an army of the just. But in a field near Babylon, Lucifer sits beneath his own dark standard. Lucifer sits astride a great throne of smoke and fire, terrible to behold and horrifying, he is surrounded by his legions. This army, like those of Sauron, in Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, “is an army bred for a single purpose: to destroy the world of men.” If, as Pope Francis, another Jesuit, often remarks, the Church is “a field hospital after battle,” Gregory Jordan was a man keenly aware of the battle that rages beneath two standards. He was also keenly aware of the Church’s place in the field of that battle. Greg took the view that this eschatological warfare was inevitable and that life was not a matter of avoiding evil, suffering, pain and loss but rather of choosing a standard and then marching under it.

Greg knew that Catholic families stand on the front lines of this warfare. Like a general in charge of a field hospital, he provided encouragement, logistical and spiritual support to families across Australia not only through his service to Jesuit Schools — from 1967 to ’73 he was Rector of St Ignatius College, Riverview; from 1974 to ’77 he was Headmaster of St Aloysius College, Milsons Point — but also in his friendship with and service of the young, especially university students — from 1978 to ’86 Greg was Rector of St John Fisher College, University of Tasmania, Chaplain to that same university in 1985 and Chaplain to the Newman Association, The Friends of the Prisoners Association and Catholic Adult Education; from 1992 to ’98 he was Rector of St Leo’s College, University of Queensland, and at various times Assistant College & University Chaplain.

Soldier for Christ

As it happens, Hamilton East, New Zealand, is about as close as one can physically come to Tolkien’s Hobbiton, being about an hour’s drive from where Peter Jackson filmed his Lord of the Rings trilogy. In this peaceful rural landscape, Gregory Fraser Jordan was born in 1930 before moving to Australia to complete his Novitiate in Watsonia, Victoria, from 1948 to ’53; his Regency at St Aloysius, Milsons Point from 1957 to ’59 and his Theologate at Canisius College, Pymble between 1960 and ’63. Gregory also studied abroad in Brussels in the year 1965. He was not a particularly tall man but he was always the life of the party and this one hobbit came to know literally thousands of people in his adopted homeland whilst always maintaining a great intimacy with his extensive family in the “Land of the Long White Cloud.”

His work as diocesan exorcist and his chaplaincy work with the St Gregory’s Latin Mass Community, the Medical Guild of St Luke, The Apostles of Mary and the Australian Catholic Students’ Association over the years from 2002 up until his death made him a household name in countless home schools, university colleges, shared flats, student houses and doctors’ surgeries across Australia. He could remember all manner of people, and their intricate familial connections, tracing seemingly anonymous persons through generations to connections with dignified persons of worth. But therein lay the rub; for all who marched under the banner of Christ were of worth to Gregory Jordan and he delighted in the achievements of his former students, many of whom returned to him to be married and to have their children baptised. He was not only the spiritual father to a score of Catholic marriages and families, but also to a significant battalion of priests.

I was a graduate of the Rev Fr Gregory Fraser Jordan Officer Training Academy, and I can point to a number of young priests of my own generation who also earned their pips under the influence of Greg Jordan. I first met Greg as an Arts/Law student at the University of Queensland in 1998. There was a group of students who regularly attended Mass at the Catholic Colleges on campus who came under the influence of “the good Jesuit,” as he was called by a great mutual friend who himself converted from the Anglican Church in the course of his university chaplaincy, and became a Catholic Priest during my time at the University of Queensland. It was through Greg’s chaplaincy at the university that I was introduced to the Extraordinary Form of the Roman Rite of Mass and to Gregorian Chant as a liturgical and spiritual art form. If that were all that I might thank the man for, it would in itself be enough to cherish his memory for a lifetime.

He dies

On the occasion of Gregory’s eighty-third birthday, I rang him to wish him well. The last thing he said to me was “Be a good priest.” Three days later, on the nineteenth of July 2015, he died; sixty-seven years a Jesuit (having entered the Society of Jesus in 1948), fifty-two years a priest (having been ordained in 1963) and forty-eight years in final vows (having made those vows in 1967). At the time of his death, there was no other priest alive who had been more influential upon the ruling political caste of Australia. Many of the Abbott Government’s Cabinet had been educated by Gregory Jordan and he was no stranger to members on the other side of the Parliamentary Chamber.

The war goes on. There are forces in our ambient culture, hostile to our faith and/or more subtly corrosive of Christian souls. Darkness spreads across the land that threatens even the most isolated of Shire-lings. Be it a fundamentalist theistic caliphate that extols voluntarism and wills that all men conform — if necessary by force and fear — to a wrathful God; or a secular caliphate that longs to eradicate all Judeo-Christian belief from our law, institutions, culture and ultimately our hearts; the Two Towers now stand in opposition to the lofty Cross. One tower is wrapped in the fiery eye of a wrathful god, the other commands rank upon rank of infuriated creatures led astray by a misguided hatred and an ignorance of what is really True, Beautiful and Good.

In this 100th anniversary of the ANZAC campaign we would do well to heed St Paul’s advice to the Ephesians (6:12-18) and “gird our loins,” in the words of the Most Rev Anthony Fisher OP; “with the camo pants of Truth, our chests with the khaki of Righteousness, our feet with the boots of Peace, our heads with the helmet of Salvation, with Faith as our flack-jacket and the Spirit as our gun.” Gregory Jordan, himself an ANZAC of a kind, a soldier of Christ both in Australia and New Zealand, knew this to be true. A general who loved his troops, Greg could see the battle looming and he braced each and every one of his troops for the onslaught. Yet, indefatigable to the last he maintained an optimism and a hope, founded on Christ, that Christians were ultimately on the winning side and that they fight for a prize in this world that shall not pass away in the next (1 Cor 9:25). Vale magister meum, requiescat in pace.

“I know. It’s all wrong. By rights we shouldn’t even be here. But we are. It’s like in the great stories, Mr Frodo. The ones that really mattered. Full of darkness and danger they were. And sometimes you didn’t want to know the end. Because how could the end be happy? How could the world go back to the way it was when so much bad had happened? But in the end, it’s only a passing thing, this shadow. Even darkness must pass. A new day will come. And when the sun shines it will shine out the clearer. Those were the stories that stayed with you. That meant something, even if you were too small to understand why. But I think, Mr Frodo, I do understand. I know now. Folk in those stories had lots of chances of turning back only they didn’t. They kept goin’. Because they were holding on to something . . . That there’s some good in this world, Mr Frodo. And it’s worth fightin’ for.”