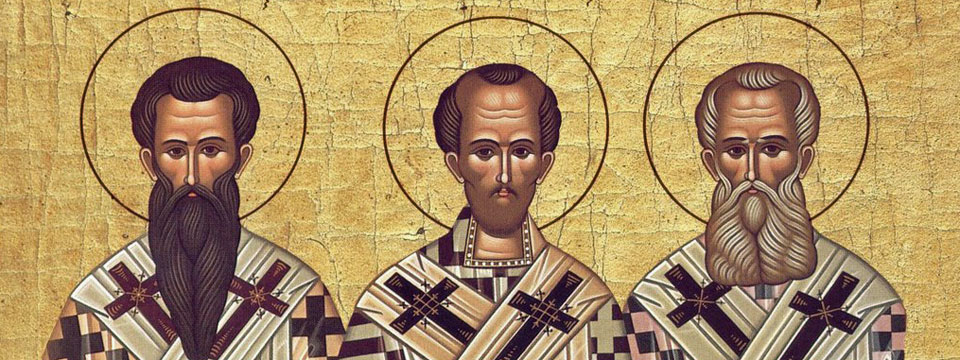

While each treatise represents a distinct literary genre (the De fuga is an apologia preached before a liturgical assembly; the De sacerdotio recounts a dialogue between two friends; and the Regula Pastoralis is ostensibly a letter to John, the Bishop of Ravenna), all three treat a similar theme: flight before the office of priest and bishop. Each author defends his reluctance to accept ordination on the grounds that the sacerdotal office entails such great responsibilities and involves tremendous risks. Each Church Father likewise expresses his deep appreciation for the contemplative life from which he had been called in order to assume the pastoral care of souls.

Gregory of Nazianzus pines for the banks of the river Iris in the province of Pontus where he once shared the companionship of Basil the Great in monastic seclusion. John Chrysostom recalls the tranquillity of the monastic hermitage which he had previously enjoyed. Gregory the Great has only to look across the rooftops of the Eternal City to the Caelian hill where stands the monastery dedicated to Saint Andrew which he founded on the grounds of his family’s estate. While a strongly contemplative dimension is present in these works, in no way does it detract from their masterful elaboration of the pastoral life. Indeed, these three treatises form what one scholar has rightly called a “pastoral trilogy.”{{1}}

Gregory of Nazianzus preached his apologia shortly after Easter of 362, having only recently returned from the monastic setting to which he had fled the year before after his “forced” ordination to the priesthood at the hands of his father, the Bishop of Nazianzus. While the dating of Chrysostom’s De sacerdotio remains an open question, modern scholarship generally attributes the treatise to the early years of his priestly ministry in Antioch; that is, between the years 388 and 390. Gregory the Great wrote the Regula Pastoralis at the very beginning of his pontificate during the months between September of 590 and February of 591. Today, we might be tempted to call it his first Encyclical Letter. In the dedicatory preface to part one, Gregory frames his opus as a response to John of Ravenna who had rebuked the Roman Pontiff for his initial hesitation in assuming episcopal office.

Our three patristic texts contain numerous themes: the demands of the pastoral life, the art of preaching, the tremendous responsibility of the ordained, the condemnation of clerical ambition, the scandalous behaviour of some members of the clergy, and the extraordinary virtue of the ideal priest. Each text merits a close reading. With you this morning, I wish simply to consider three overarching themes: priestly ministry, priestly life and priestly witness. Our three Church Fathers hold that effective ministry flows from a life of priestly virtue which, given the priest’s public witness, must be exemplary. Without the latter, they argue, the former is greatly impaired. Although the Augustinian notion given medieval expression in the phrase ex opere operato is not explicitly found in these texts, neither is it necessarily contradicted. But given the authors’ implicit aim to present an exalted image of the priesthood in order to counteract clerical mediocrity and sinfulness, the emphasis is squarely placed upon the priest himself and the tremendous responsibility of his sacred office.

Priestly Ministry

Munus regendi

We find in these three patristic texts the triple munera of the priestly office: the munus regendi, the munus docendi and the munus sanctificandi. Gregory of Nazianzus calls the munus regendi, or duty of pastoral governance, “the art of arts and the science of sciences.”{{2}} This art entails a ministry of healing. The priest governs in order to cure souls. Indeed, for Gregory, the munus regendi is explicitly at the service of the munus sanctificandi. Inasmuch as the soul is superior to the body, the priestly physician is superior to the ordinary medical doctor. He is likewise superior to those whom he governs. Right order and the beauty of the Church demand such. Before the priest can engage in his ministry of spiritual healing for the good of others, he himself must first have recovered from his own spiritual malaise. It is not so much a matter of “Physician, heal thyself”, as it is one of “Be healed before attempting to heal.” “The scope of our art”, Gregory explains,

is to provide the soul with wings, to rescue it from the world and give it to God, and to watch over that which is in His image, if it abides, to take it by the hand, if it is in danger, or restore it, if ruined, to make Christ to dwell in the heart by the Spirit: and in short, to deify, and bestow heavenly bliss upon, one who belongs to the heavenly host.{{3}}

Thus the priest’s pastoral governance hierarchically ordained by God stands at the service of the flock’s salvation.

For his part John Chrysostom envisions the priesthood as an angelic ministry exercised by men on earth for the good of souls. He specifically notes that “The divine law excluded women from this ministry”4 and he insists that ? given the magnitude of the task ? most men should stand aside as well. The Holy Spirit and he alone has ordained the priestly succession, persuading “men, while still in the flesh to represent the ministry of angels”.{{5}} But the priestly authority to bind and loose sinners exceeds even the powers granted to the angelic host. Indeed, no greater authority on earth has been given to man. For, by it the priest opens the gates of heaven to the sinner.{{6}}

Echoing Gregory of Nazianzus, Pope Gregory the Great instructs that ars est artium regimen animarum, “the government of souls is the art of arts”.{{7}} Duly rebuked by John of Ravenna, the Roman Pontiff humbly embraces the Divine Will made manifest to him in his election to the papacy, noting that genuine humility “is not obstinate in declining to undertake what is enjoined to be profitably undertaken.”{{8}} The first to adopt the papal title servus servorum Dei, Gregory envisions the ecclesiastical hierarchy in terms of pastoral service for the sake of preaching and fraternal correction. While all men enjoy equality on account of a common human nature, they differ in terms of vice. “Wherefore,” Gregory admonishes, “all who are superiors should not regard in themselves the power of their rank, but the equality of their nature; and they should find their joy not in ruling over men, but in helping them…. Supreme rank is, therefore, well-administered, when the superior lords it over vices rather than over brethren.”{{9}} To this end, the munus regendi employs the munus docendi.

Munus docendi

The priest serves the people, the Cappadocian Gregory acknowledges, by instructing them in the faith and defending the truth. John Chrysostom insists that the preacher be simultaneously skilful in speech and humble in spirit. He should possess the force of eloquence all the while holding praise in contempt. He should seek God’s glory and not his own before men. “It will be sufficient encouragement for his efforts,” John explains, “and one much better than anything else, if his conscience tells him that he is organising and regulating his teaching to please God.”{{10}}

Pope Gregory teaches that the pastor should preach virtue and, as we have already observed, attack vice. He should begin by preaching to himself, as it were, and reforming his own life. In this way he will first proclaim by his deeds what he intends to preach to the people.{{11}} Concomitant with the ministry of preaching stands a ministry of compassion. The pastor lovingly transfers to himself the infirmities of others. Just as by means of contemplation he comes to aspire to heavenly things, so too by means of compassion he comes to share in the burdens of the weak. In this way he makes himself accessible to sinners, enabling them to approach him and to open their consciences to him without fear. Preaching thus leads to the munus sanctificandi.

Munus sanctificandi

The priest exercises the munus sanctificandi above all through his administration of the Sacraments, which could not be performed without him. Thus, Gregory of Nazianzus rhetorically inquiries, “where, and by whom would God be worshipped among us in those mystic and elevating rites which are our greatest and most precious privilege, if there were neither king, nor governor, nor priesthood, nor sacrifice, nor all those highest offices?”{{12}} By Baptism the priest renews the human creature, sets forth the divine image and creates inhabitants for the world above. Ministering the divinizing gift of salvation, he “make[s] others to be God.”{{13}} His cultic role at the Eucharist especially reveals his share in Christ’s priesthood. Serving at the Altar he stands alongside angels and archangels and causes “the sacrifice to ascend to the altar on high.”{{14}} His is an awesome responsibility to say the least, and it requires the greatest virtue. “When [the priest] invokes the Holy Spirit and offers that awful sacrifice and keeps on touching the common Master of us all, tell me, where shall we rank him?” the Golden-mouth Preacher asks:

What purity and what piety shall we demand of him? Consider how spotless should the hands be that administer these things, how holy the tongue that utters these words. Ought anyone to have a purer and holier soul than one who is to welcome this great Spirit? At that moment angels attend the priest, and the whole dais and the sanctuary are thronged with heavenly powers in honour of Him who lies there.{{15}}

Priestly Life

Personal purification

Given the priest’s awesome responsibility to “make others to be God”{{16}} through his administration of the Sacraments, Gregory of Nazianzus insists that the priest must above all else be God, as it were, in order to do what God alone can truly do. Such divine conformity ought to reveal itself in a life of exemplary virtue. On this account, the priest’s personal purification necessarily precedes his priestly ministry. As the Cappadocian Father counsels:

A man must himself be cleansed before cleansing others: himself become wise, that he may make others wise; become light, and then give light; draw near to God, and so bring others near; be hallowed, then hallow them; be possessed of hands to lead others by the hand, of wisdom to give advice.{{17}}

Gregory effectively argues that the priest can only give what he himself first possesses. In this light, Gregory appeals to Romans 12:1-2 and Psalm 51, the Miserere. If the priest wishes to serve God worthily, especially in offering the Holy Sacrifice, then, he must first offer himself as a holy living sacrifice truly pleasing to God. Only with a humble and contrite heart can the priest hope to offer a fitting sacrifice of praise. For “how could I dare to offer Him,” Gregory queries, “the external sacrifice, the antitype of the great mysteries, or clothe myself with the garb and name of priest, before my hands had been consecrated by holy works?”{{18}}

Pre-eminence in virtue

Not simply free from sin, the priest must also be preeminent in virtue for the sake of his ministry in the service of souls. As Gregory explains:

In the case of a ruler or leader it is a fault not to attain to the highest possible excellence, and always make progress in goodness, if indeed he is, by his high degree of virtue, to draw his people to an ordinary degree, not by the force of authority, but by the influence of persuasion.{{19}}

In this regard, priestly virtue has an explicitly apostolic dimension. Gregory illustrates his point with an allusion to Christ who, in instructing his disciples, insisted that “the gospel should make its way, no less by their character than by their preaching.”{{20}} Similarly, the priest exhorts more by means of his deeds than by his words. Thus by his own personal example does he raise high the bar of virtue after which the members of his flock should strive. In sum, the priest is called to a higher standard of virtue for the sake of those whom he serves.

In the De sacerdotio John Chrysostom juxtaposes the virtue of the priest with that of the monk. Recall that monastic life in the fourth century was primarily a lay reality. Monks were generally not priests. While not utterly incompatible with the monastic vocation, priesthood with its concomitant apostolic duties was seen to impede the purely contemplative character of monastic life. The monks of the Egyptian desert did not look all that favourably upon a confrere’s sacerdotal ordination. In some respects they viewed it as a betrayal of his monastic vocation, for it entailed a certain return to the world ? worse yet, if it arose from his own worldly ambitions. Pining for the safe harbour of the monastic cell, which he had enjoyed for some years, John depicts his own personal struggles with a call to the priesthood which came to him through the local Church. He is dramatically aware of the challenges, not to mention, dangers, which it entails. Whereas the monk need only be concerned for his own salvation, the priest is also accountable for the ecclesial community entrusted to his care. Given the priest’s greater responsibility, failure in his pastoral duty merits a commensurate punishment.

Priestly discipline

Because the priest must face so many temptations while both being in the world and striving not to be of it, he must be even more vigilant than the hermit in his hermitage who, John notes, is, in fact, extremely vigilant. In order to combat such worldly temptations, the priest has need of even greater purity than the monk. He must engage in unremitting self-denial and strict self-discipline. In contrast to the monk, however, he more properly mortifies his will rather than his body. While the monk may engage in various external ascetical practices, the priest does best to temper his heart: “For it would not harm the common life of the Church if a prelate should neither starve himself of food, nor go barefoot. But a furious temper causes great disasters both to its possessor and to his neighbours.”{{21}} A holy priest in the world, that is, a true contemplative-inaction, ultimately merits John’s highest praise. Such priests are “those who mix and associate with all sorts of people and still manage to preserve more untarnished and steadfast than the monks themselves their purity and poise, their devoutness, patience, and frugality, and the other good qualities that belong to monks.”{{22}}

Echoing again Gregory of Nazianzus, Pope Gregory the Great insists that a prelate’s conduct should far surpass that of his flock: “he should be pure in thought, exemplary in conduct, discreet in keeping silence, profitable in speech, in sympathy a near neighbour to everyone, in contemplation exalted above all others, a humble companion to those who lead good lives, erect in his zeal for righteousness against the vices of sinners.”{{23}} His sacramental ministry of reconciliation requires that he be pure if he hopes to purify others. “A man who is debased by his own guilt,” the Roman Pontiff admonishes, “must not intercede for the faults of others.”{{24}} “No impurity should stain one who has undertaken the duty of cleansing the stains of defilement from the hearts of others as well as from his own.”{{25}} The same holds true for the celebration of the Eucharist inasmuch as it, too, is a sacrament of forgiveness: “Whosoever, then, is subject to any of the aforesaid defects [namely; pride, avarice and lust], is forbidden to offer loaves of bread to the Lord. The reason is obvious: a man who is still ravaged by his own sins, cannot expiate the sins of others.”{{26}} Yet the Pope concludes elsewhere that spiritual perfection

is providentially beyond the grasp of the man called to rule others. God, in fact, leaves the minds of such men imperfect so that “when they are resplendent with extraordinary attainments, they may grieve with disgust for their imperfections, and, least of all, exalt themselves for great things, when they have to labour and struggle against very small matters.”{{27}} Humility on account of small yet persistent failings prevents one from taking pride in great accomplishments.

Pope Gregory exhorts priests to live model lives, and by their lives to set the standard for love. Theirs is to be a well-ordered interior life. Having died to all sinful passions, they should be spiritually inspired men. While not coveting the goods of others, they should be generous in giving of their own. The compassionate heart of the priest should be prompt to forgive yet balanced in forgiving. He should deplore unlawful acts while being sympathetic to the frailties of others. “In all that he does,” Pope Gregory concludes,

he sets an example so inspiring to all others, that in their regard he has no cause to be ashamed of his past. He so studies to live as to be able to water the dry hearts of others with the streams of instruction imparted. By his practice and experience of prayer he has learned already that he can obtain from the Lord what he asks for, as though it were already said to him, in particular, by the voice of experience: When thou art yet speaking, I will say, “Here I am.”{{28}}

Priestly Witness

Gregory Nazianzus

The priestly image, which our three Church Fathers present us, is acknowledgedly an ideal. Gregory of Nazianzus is quick to point out that such a priest is not formed overnight. Indeed, such idealism sent shivers down his own sacerdotal spine. Filled with a profound sense of unworthiness upon his ordination to the priesthood, he immediately fled from his pastoral duties and returned to the monastic retreat which he had shared with his friend and fellow Cappadocian, Basil the Great. But Gregory fled not only because of his own sense of personal unworthiness, but also because of the woefully scandalous behaviour of some priests. Their notable lack of virtue filled him with dread. “I was ashamed of all those others,” he writes,

who, without being better than ordinary people, nay, it is a great thing if they be not worse, with unwashen hands, as the saying runs, and uninitiated souls, intrude into the most sacred offices; and, before becoming worthy to approach the temples, they lay claim to the sanctuary, and they push and thrust around the holy table, as if they thought this order to be a means of livelihood, instead of a pattern of virtue, or an absolute authority, instead of a ministry of which we must give account. In fact they are almost more in number than those whom they govern; pitiable as regards piety and unfortunate in their dignity.{{29}}

Gregory criticises those who degrade priestly ministry by reducing it a form of secular employment. Failing to recognise the sanctifying service which priesthood entails, such worldly priests exercise their ministry in an authoritarian manner. Sadly, their own vice quickly infects their subjects as well. Alluding to the prophet Ezekiel’s diatribe against unfaithful shepherds, Gregory decries not only those among the clergy who sin, but also those leaders who whitewash the sins committed by others. According to Gregory, Ezekiel “threatens that [God] will consume both the wall [that is, the sin which divides] and them that daubed it (cf. Ezek. 13:14); that is, those who sin and those who throw a cloak over them; as the evil rulers and priests have done.”{{30}}

John Chrystostrom

Priestly scandal brings home that obvious fact which is best never forgotten: the priest is a public figure. He cannot escape notice. “The priest’s shortcomings simply cannot be concealed,” John Chrysostom insists,

On the contrary, even the most trivial soon get known…. The sins of ordinary men are committed in the dark, so to speak, and ruin only those who commit them. But when a man becomes famous and is known to many, his misdeeds inflict a common injury on all.{{31}}

There are those, John observes, who will never tire of searching the lives of priests for even the slightest impropriety:

For as long as the priest’s life is well regulated in every particular point, their intrigues cannot hurt him. But if he should overlook some small detail, as is likely for a human being on his journey across the devious ocean of this life, all the rest of his good deeds are of no avail to enable him to escape the words of his accusers. That small offence casts a shadow over all the rest of his life. Everyone wants to judge the priest, not as one clothed in flesh, not as one possessing a human nature, but as an angel exempt from the frailty of others.{{32}}

Gregory the Great

The priest’s public persona arises from both his sacred duties and the earthly affairs to which his ministry inevitably calls him. Drawing upon his own experience, Pope Gregory the Great observes that the prelate in particular cannot wholly escape worldly affairs. He warns, nonetheless, that the priest must be attentive not to resign himself totally to such secular matters, for they tend to diminish his holiness and the reverence that others have for him. Secularly minded clerics prove to be stumbling blocks for the spiritual growth of their subjects. “Indeed,” the Pope poetically observes, “the stones of the sanctuary lie scattered through the streets, when persons in Sacred Orders, given over to the laxity of their pleasures, cling to earthly affairs.”{{33}} Gregory proposes a properly balanced approach to earthly affairs. To illustrate his point, he describes the moderation to be exercised in sacerdotal coiffures:

Since … all who are placed over others should, indeed, have a care of external matters, but without being excessively occupied with them, priests are rightly forbidden to shave the head, or let the hair grow long, that so they may not wholly discard all consideration for the flesh on behalf of the lives of their subjects, nor again, allow it to engross them too much … hairs on the head of the priest are kept to cover the skin, but are cut away, so as not to veil the eyes.{{34}}

Conclusion

Agere sequitur esse ? acting follows being. According to this Thomistic axiom, being is the cause of acting, and acting is the effect of being. At the risk of sounding anachronistic, I wish to venture that this Scholastic axiom summaries well the patristic vision of priesthood found in the pastoral trilogy which we have been considering. Priestly ministry follows priestly life.

While the Cappadocian and Roman Gregories, along with the Antiochene Preacher John, do not address the question of a sacrament’s validity when it is administered by a sinful cleric, they do place great emphasis upon the need for priestly virtue in a coherent priestly ministry. They are quick to condemn in the preacher the pharisaical attitude of “do what I say, but not what I do.” They recognise that the priest must first be the priest who he has been ordained to be before engaging in pastoral ministry. His living an extraordinarily virtuous life greatly enhances his sacerdotal service of the faithful, and in some respects is essential to it. For, a contrary witness on the part of the priest effectively undermines the good of his ministry. As we are all too well aware in our own day, priestly scandal places an immense stumbling block on the faithful’s path towards the Lord.

Rather than despair before the priestly ideal which this patristic pastoral trilogy presents us, I propose that we priests can benefit from it in at least three respects. Firstly, it rightly calls us before all else to confess our own sinfulness and to seek the Lord’s mercy in our lives so that our proclamation of Christ’s mercy to others may not, itself lacking love, clang in their ears like mere pious platitudes, but rather arise directly from our own immediate experience of Christ’s saving grace. Secondly, we should never cease with the help of Christ’s grace to strive after perfection not for our own sake, which would egotistically threaten to undermine the very perfection we seek, but rather for the sake of those whom we serve. For we realise that our deeds do, in fact, preach louder than our words. The faithful have need of holy priests faithful in their own lives to the Gospel which they preach. By their holy witness such priests serve God’s people best. Finally, in an age that has tended to reduce the priesthood to a merely functional reality, it is paramount to reclaim a properly ontological understanding of priestly life ? an ontology underlying all priestly ministry. For, as Gregory of Nazianzus, John Chrysostom and Gregory the Great rightly acknowledge, effective priestly ministry does indeed flow forth most graciously from a life of priestly virtue.

[[1]]Cf. B. H. Vandenberghe, Introduction à Saint Jean Chrysostome, Dialogue sur le sacerdoce (les Écrits des saints), Namur 1958, p. 25; see also: Bruno Judic, “Introduction,” Grégoire le Grand: Règle Pastorale, vol. 1, Sources Chrétiennes 381, p. 34.[[1]]

[[2]]Gregory of Nazianzus, Oration 2, Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Second Series, vol. VII, trans. cHarles gordon Browne & James edward swallow (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1978), De fuga 16 (Sources Chrétiennes (= SC) v. 247, p. 110).[[2]]

[[3]]Gregory of Nazianzus, De fuga 22 (SC 247, 118-120).[[3]]

[[4]]John Chrysostom, Six Books on the Priesthood, trans. graHam neVille (Crestwood: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1984), De sacerdotio 3.9, p. 78 (SC 272, 162); NB Given a discrepancy in the numerical classification between the critical edition and the English translation, the book and chapter numbers follow Sources Chrétiennes, and the page numbers indicate where the text can be found in the St Vladimir Seminary Press’ English translation.[[4]]

[[5]]John Chrysostom, De sacerdotio 3.4, p. 70 (SC 272, 142).[[5]]

[[6]]John Chrysostom, De sacerdotio 3.5, pp. 71-74 (SC 272, 146-150).[[6]]

[[7]]Gregory the Great, Pastoral Care, trans. Henry Davis, SJ, Ancient Christian Writers, no. 11 (New York: Newman Press, 1950), Regula Pastoralis 1.1 (SC 381, 128).[[7]]

[[8]]Gregory the Great, Regula Pastoralis 1.6 (SC 381, 148).[[8]]

[[9]]Gregory the Great, Regula Pastoralis 2.6 (SC 381, 204; 210).[[9]]

[[10]]John Chrysostom, De sacerdotio 5.7, p. 133 (SC 272, 298).[[10]]

[[11]]Cf. Gregory the Great, Regula Pastoralis 3.40 (SC 382, 530-532).[[11]]

[[12]]Gregory of Nazianzus, De fuga 4 (SC 247, 92).[[12]]

[[13]]Gregory of Nazianzus, De fuga 73 (SC 247, 186).[[13]]

[[14]]Ibid.[[14]]

[[15]]John Chrysostom, De sacerdotio 6.4 (SC 272, 316), pp. 140-141.[[15]]

[[16]]Gregory of Nazianzus, De fuga 73 (SC 247, 186).[[16]]

[[17]]Gregory of Nazianzus, De fuga 71 (SC 247, 184).[[17]]

[[18]]Gregory of Nazianzus, De fuga 95 (SC 247, 212-214).[[18]]

[[19]]Gregory of Nazianzus, De fuga 15 (SC 247, 110).[[19]]

[[20]]Gregory of Nazianzus, De fuga 69 (SC 247, 182).[[20]]

[[21]]John Chrysostom, De sacerdotio 3.10 (SC 272, 176), p. 83.[[21]]

[[22]]John Chrysostom, De sacerdotio 6.8 (SC 272, 330), p. 146.[[22]]

[[23]]Gregory the Great, Regula Pastoralis 2.1 (SC 381, 174).[[23]]

[[24]]Gregory the Great, Regula Pastoralis 1.11 (SC 381, 164).[[24]]

[[25]]Gregory the Great, Regula Pastoralis 2.2 (SC 381, 176).[[25]]

[[26]]Gregory the Great, Regula Pastoralis 1.11 (SC 381, 172).[[26]]

[[27]]Gregory the Great, Regula Pastoralis 4.1 (SC 382, 538-540).[[27]]

[[28]]Gregory the Great, Regula Pastoralis 1.10 (SC 381, 162).[[28]]

[[29]]Gregory of Nazianzus, De fuga 8 (SC 247, 98-100).[[29]]

[[30]]Gregory of Nazianzus, De fuga 65 (SC 247, 178).[[30]]

[[31]]John Chrysostom, De sacerdotio 3.10 (SC 272, 180-182), p. 85.[[31]]

[[32]]John Chrysostom, De sacerdotio 3.10 (SC 272, 182-184), p. 86.[[32]]

[[33]]Gregory the Great, Regula Pastoralis 2.7 (SC 381, 224).[[33]]

[[34]]Gregory the Great, Regula Pastoralis 2.7 (SC 381, 230).[[34]]