The crisis in catechesis

It is now widely acknowledged that the religious education of children in the Catholic tradition has posed challenges for nearly many years. Some may be tempted to believe that the solution might lie in a return to the strategy of the Penny Catechism – committing to memory the doctrines of the Church, compressed into accurate propositions.

It is easy to forget that this practice, when pursued in isolation, had already drawn valid criticism in the pre-conciliar period. Cardinal Henri de Lubac, for example, referred to a serious problem with it as early as 1942. He claimed that the idea of compressing the sublime reality of God into a series of Catechism answers was clearly inadequate, since it had an inherent tendency to rationalise the mystical element of faith:

A doctrine without mystery, a moralism deprived of any mystical element, cannot satisfy a soul that has, despite everything, remained religious. If therefore the sense of mystery and the sense of the sacred come to be lacking, something else would have to be found to replace them. These are often found, it seems to me, in a certain sentimentalism, which is characterized notably by the abuse of devotions.{{1}}

Here, in a nutshell, de Lubac identified the problem. Can any human mind contain the immensity of God? It is reminiscent of Augustine’s encounter with the child trying to pour all the waters of the sea into a tiny hole in the sand. Those, like me, who have happy memories of their pre-Conciliar religious education would quickly realise that what was good about it was never just the memorisation of pre-digested answers.

No, what made it come alive for us was the person who presented it. These people were usually religious who were living sacrificial lives in communities of faith nourished by regular prayer and daily celebration of the Eucharist. With passionate commitment, they could present the faith attractively and vibrantly – through stories of the saints and the great moments of Catholic history, a love of prayer and the sacraments, and a capacity to connect with and inspire young minds.

In other words, they found a way to introduce us to Christ himself. Many of these good catechists had already begun to realise the power of the Scriptures and the Liturgy as they embraced the Kerygmatic approach to religious education in the early 1960s. It is perhaps distressing to recall the way in which this promising development was hastily set aside as the catechetical catastrophe known as experiential catechetics rolled in and swept all before it.

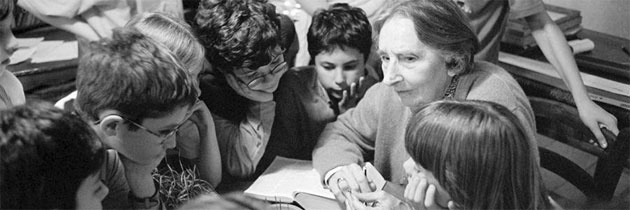

Sofia Cavalletti

Not everyone, however, was swayed by this particular siren call. Sofia Cavalletti, who was to become one of the best catechetical theorists of this or any other time, was a notable exception. Cavalletti was an unlikely starter in the field that became her own. She had little to do with children until her thirties, and her first love had been the Scriptures.

The young Sofia Cavalletti studied at the Sapienza University under Eugenio Zolli – former chief rabbi of Rome during World War II, and a convert to Catholicism afterwards. Cavalletti became a first rate scholar of the Scriptures and of the Hebrew language. She was a little bemused when asked to prepare a child for his First Communion in 1954, but accepted the challenge. What astonished her was that the seven year old boy, Paolo, was profoundly moved by her presentation of the Creation stories from Genesis. He did not want to leave, even after two hours! The encounter alerted Cavalletti to the attraction children feel towards the Scriptures, simply presented. She confirmed in practice the theoretical insights of de Lubac. The real solution to the catechetical problem lay in the retrieval of mystery – of the sense of the sacred. But how was this insight to be incorporated into a real-world program?

This need for practical solutions lead her to explore the educational insights of Maria Montessori, and it was through this interest that Cavalletti began collaborating with one who was to work with her for the rest of her life in developing the Catechesis of the Good Shepherd – Gianna Gobbi, a professor of Montessori education. Together, they painstakingly adapted Montessori principles to the Religious education of children.

Three key themes were to emerge as the cornerstones of their approach: Scripture, Liturgy and Mystagogy. Both observed that children responded profoundly to the concrete realities and mystical meanings contained in the Scriptures and the Liturgy. Through these, they are able to enter into the mystery of Christ through the celebration of the Sacraments.

Catechesis of the Good Shepherd

Cavalletti and Gobbi took as their starting point the developmental stages articulated by Montessori and developed the implications of these for religious education.

Stage 1

In broad outline, they discovered that, in the first of these (ages three – six years) children are focused on the need for love, care and protection. It is for this reason that they relate closely to the parable of the Good Shepherd. They are also drawn to the major themes in the life of Jesus. Furthermore, these young children seemed to learn best when they were offered real objects. Hence, they developed concrete materials associated with the liturgy, and dioramas depicting the scenes and characters in the major Scriptural narratives and parables.

Stage 2

In the second stage (ages six – nine years) the focus turns to seeking out the relationship that exists between the disparate things that children have already discovered: the sequencing of various elements of salvation history, the purpose of each of the liturgical materials and the moral maxims of Jesus.

Stage 3

A further stage (ages nine – twelve years) develops the relationships discovered in stage two, and begins to seek out the ‘lived experience’ of these things expressed in the lives of those who are guiding them and in the lives of the saints.

Cavalletti was no starry-eyed theorist. She and Gobbi were determined to be led by the children and by the God who drew them to himself. They experimented with large numbers of materials over more than 50 years. Never would they only allow any of these works to remain on their shelves if the children were not genuinely drawn to them.

Cavaletti’s grand ancestral home – in which three large rooms were devoted to the works of Catechesis of the Good Shepherd – was a beacon for her collaborators around the world. She had time for everyone who came there. I visited once in 2009, and was moved by her gracious words to me and her willingness to let strangers from half way around the world walk through her home and breathe the atmosphere of a place made holy by its dedication to God and to children.

The natural way of learning

After these many years of patient experimentation, Cavalletti understood the key principles that must underlie any successful catechetical approach – in reviewing them now, one could almost be excused for thinking that she had made a thorough study of the works of St Thomas Aquinas.

According to Cavalletti, the truth about God is best mediated through the concrete analogies found in the Scriptures and the Liturgy. One of her enduring catechetical principles, put succinctly, was this: First the body, then the heart and finally, the mind.

“First the body . . .”

Cavelletti came to understand through sustained observation that when a child begins to learn something new, the starting point is not the mind, but the senses.{{2}} When applied to the catechesis of the youngest children, this means using concrete materials to present the Scriptures and small models of liturgical vessels, linens, furniture etc. Through this means, children are drawn into wonder, which Cavalletti claims is evoked by “an attentive gaze at reality.”

“. . then the heart . . .”

Once the senses have done their work and created a degree of healthy curiosity, the focus moves to strategies for winning over the heart of the child. It is at this point that attention is given to the actual words of Scripture, reflecting Cavalletti’s initial practical insight into what attracts the hearts of children. Hand in glove with this is the effort that must go into creating the atmosphere for prayer. Ultimately, this is a work of grace and Cavalletti humbly acknowledged this dimension of all her catechetical work.

“. . and finally the mind.”

Finally, when the experience of the senses and the heart have had an opportunity to do their work, it is time to move on to the compressed doctrinal formulations – to put appropriate words in place for the mind to grasp. The words, however, should express a great reality lying behind them in the senses and the hearts of those who have had time to ponder the mystery. They will then understand that the words do not exhaust the meaning of the mystery. There will be more implications to unpack; there will be more words needed later to express their further reflections on the great mysteries to which they have been introduced.

Clearly this approach is the opposite of starting with propositions and then explaining them. Of course, many of us know from our experience that it is certainly possible to start with definitions and still arrive at a deep and lasting faith – especially if the one offering the explanations is embodies and breathes the love of God. When the Cure of Ars explained his catechism, it might be argued that it was his own life and evident love which was doing the preaching!

Yet it must be acknowledged, as Cavalletti realised, that all will work much better if one follows the natural human way of learning. As St Thomas noted, “knowledge is in the knower according to the mode of the knower.” Cavalletti, then, articulated a way to give full force to both the mystery and the doctrinal soundness required of an authentic program of catechesis. This is what she incorporated into the Catechesis of the Good Shepherd.

An ongoing legacy

There is one further remark that must be made. Those who knew Sofia Cavalletti were always struck by her evident holiness and simplicity. Despite the wide popularity of her work, she willingly and freely shared what she had, wanting only to see children come closer to their Lord. She genuinely believed that she was receiving from them much more than she was giving.

To the very end her long life of ninety-four years, she remained capable of being enchanted by the discoveries of children encountering the love of their God. During a celebrated visit to her catechetical centre in Rome, Pope John Paul II confessed that he was ‘simply amazed’ at what she had been able to achieve with children, and remarked that he would love to see parishes all over the world consider introducing an Atrium of the Good Shepherd.

The Catechesis of the Good Shepherd has now spread to thirty-eight countries, including Australia. Cavalletti has written a number of books which have articulated her mature understanding of various aspects of her work. The Religious Potential of the Child sets out her principles for younger children. This is further developed for older ones in The Religious Potential of the Child Six to Twelve Years. Her liturgical reflections can be found in Living Liturgy. Perhaps her most remarkable work is the one in which she united her professional expertise as a Scripture scholar with her capacity to adapt this for children History’s Golden Thread, which has now been republished under the title of Creation to Parousia.

Yet, for those who are interested, there is a far better way of coming to know how the Catechesis of the Good Shepherd works – in the words of Christ himself, “Come and see!” Visit an atrium of the Good Shepherd and prepare to be surprised and delighted with what awaits you there. (For more information, contact the Association of the Catechesis of the Good Shepherd, Australia.)

[[1]]De Lubac, Henri. “Internal Causes of the Weakening and Disappearance of the Sacred.” Reprinted and translated in Josephimum Journal of Theology (Pontifical College Josephimum, Columbus: Ohio, Winter/Spring, 2011), p. 45.[[1]]

[[2]]This of course echoes the view of St Thomas Aquinas … “Noting in the mind that is not first in the senses.”[[2]]