Life during and after the Council

On 21st September 1963, in the company of my bishop, I arrived in Rome in the first class cabin of a Pan Am flight. (As you can imagine, since then it has all been downhill; ‘premier economy’ is little consolation.) The bishop was going to the second session of Vatican II; at his behest I went with him to work for a doctorate in theology, writing as he said, on “something concerning ecumenism.” In fact, along with the liturgical movement, the unity of Christians had been a longtime interest of mine as a seminarian and in my ten years as a priest.

Once arrived in Rome, I had to find a university and a professor under whom I could write. After a less than satisfactory visit to the somewhat choleric Dutch Jesuit who was the professor of ecumenical studies at the Gregorian, it was a relief to discover that Father Jerome Hamer, the Master of Studies for the Dominicans, also took a few doctoral students at the Angelicum; mercifully he accepted me. From my seminary days, I already knew of him and his writings on ecumenism, among other things; perhaps some of you know his book: The Church is a Communion.

In 1963 and the few years following, Rome was a wonderful place to be. Nothing was as yet perceptible of the sour mood and social unrest that followed 1968 and that turned into the frightening “Years of Lead” and produced the Red Brigades.

In the early 1960s the Council had taken over the city. This coincided with the sunny optimism that prevailed in much of the world in the 1960s. The Church was bathed in it too. To be in Rome during the Council was a vivid experience of the universality of the Church, heightened by the world’s apparent approval of what was happening in the Council.

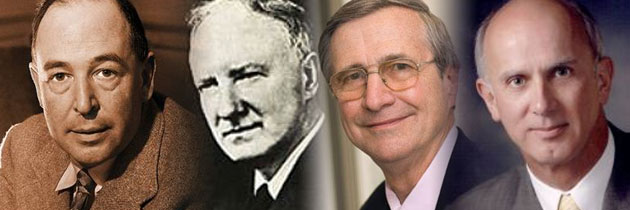

I exploited every opportunity to meet and to hear talks from so many of the great names in theology like the Englishman Charles Davis (soon however to leave Rome for Florence); Rudolph Schnackenburg; Karl Rahner; Yves Congar; Hans Kung; and many others whose writings I already knew and had been influenced by. And there was the young newly married former seminarian from the US, Michael Novak, brash and arrogant in his opinions which he embodied in the book, The Open Church. It helped that he was intelligent and so in his later life could say: “I deserve to be shamed for some of the extreme things I wrote.” By that time he had found an altogether better understanding of the Council in the writings of John Paul II and Benedict XVI.

While the event of the Council was attracting world attention it was hard to keep one’s mind on the lectures at the Angelicum, most of which took little or no notice of what was happening up the road at St Peter’s. By way of exception, a seminar given by Fr Hamer, dealt with the book Honest to God by Anglican Bishop John Robinson, which was causing a flutter among Anglicans and winning plaudits from atheists. Hamer had the ability to show understanding of what Robinson was trying to say and to evaluate it in light of Catholic teaching.

Meanwhile there were the daily reports of what had been said in the Council hall by the bishops and as well the talks given by some of the bishops and the periti and the regular press conferences which told of what the Council was doing and what the speakers hoped it might do. These were overwhelmingly from a liberal perspective; conservative speakers in the Council as reported, seemed an embattled minority. Yet now if one consults the Acta Synodalia, the verbal reports of what had been said and written by the Council, it is striking to note that, especially in the working groups which were not reported publicly, even those cardinals and bishops considered progressive showed the real concern for the teaching of the Church that one would expect from faithful Catholic bishops.

Sacrosanctum Concilium

When the Council documents began to emerge, those were exciting days. I remember one afternoon getting the Constitution on the Liturgy, Sacrosanctum Concilium, from one of the newspaper kiosks in St Peter’s Square and paging through it. A first impression was of disappointment. It was what Joseph Ratzinger later was to call “a recipe book for making sweeping changes in the form of the Church’s liturgy.” Where was the reflection from this great gathering of bishops on the theology of the liturgy, the insights into its depths? Did they not know the massive writing that had been emerging from the liturgical movement and from papal pronouncements? — especially Mediator Dei, the great encyclical of Pope Pius XII which in so many respects is more theologically weighty than Sacrosanctum Concilium. Yet one does find important theological insights in the first chapter of Sacrosanctum Concilium on the nature of the liturgy, in the too brief introductory part of chapter 2 on the mystery of the Eucharist, and in the chapters on the liturgical year and on the divine office.

The truth was, as Ratzinger later said, that the liturgy was not a prime concern of the bishops; they were largely content that the development of liturgical forms launched by St Pius X and boosted by Pope Pius XII should continue under the aegis of the Congregation of Rites, as it did right up until the beginning of the Council. They were also happy to affirm a further reform of the liturgy that, in Ratzinger’s words, would be “ a new humble and sober centering of the mystery of Christ’s presence in his Church.”

Yet unknown to most of the bishops many liturgists and some bishops who supported them had been working, before the Council and in it, to bring about far reaching changes, not all of them well founded on the best theology and traditions of Catholic worship. In Sacrosanctum Concilium they were trying to build an instrument that would re-fashion the liturgy; as Pope Benedict kept on pointing out right up to the time of his retirement, what emerged was a liturgy that, as it was presented, left us with empty churches.

Lutheran friends, a husband and wife who both taught theology in a University in Denmark, and who came regularly to Rome — as did many Scandanavians — were completely negative about the reformed liturgy as they encountered it in papal ceremonies in St Peter’s; “What an impoverishmen!” they said. Earlier I had had a similar impression at Sant’ Anselmo, the international Benedictine house, when still during the Council I had attended a private, experimental celebration of the Mass in which a form based on the Vatican II reforms was used. It was curiously flat and failed to suggest the transcendent.

A virtual or parallel Council

Of course my interest was especially in the Decree on Ecumenism, Unitatis Redintegratio, published on 21st November, 1964 after some intense discussion. On the part of some bishops there was worry lest it be a sell-out of the Church’s claims, while among a few there was a feeling of disappointment because their desire to play down the uniqueness of the Catholic Church in order to get quick results was not accepted. I viewed the Decree immediately from the perspective of the help it might be for my doctoral work.

In fact Unitatis Redintegratio gives a fairly solid theological basis for relations with other churches and ecclesial communities and, importantly, it enunciates Catholic principles on ecumenism. When the Decree calls for ecumenical action it insists that such action must be “fully and sincerely Catholic.” Had this subsequently been followed by Catholics engaged in ecumenical dialogue there would have been fewer disappointed expectations on the part of other Christians in dialogue with the Church and more genuine progress towards unity would likely have been achieved.

In those years of the Council, the Church was riding high, especially among progressives who loudly denounced triumphalism by conservatives but indulged in it themselves. The communications media had taken up the Council as a means of shaping the Catholic Church in the way they would like to see it develop; so they gave the Council and their interpretation of it worldwide exposure. Just before he retired Pope Benedict spelled out the price the Church has paid for this; the media presentation of it, he suggested, became a kind of virtual or parallel council which, with great success, was able to put a spin on what it reported of the Council’s teaching; they depicted it as a political event, a battle being fought out between liberals and conservatives.

This massive misinterpretation of what the Council was trying to do and to teach still influences the simplistic views of the media today; it also dogs the efforts of the Church to use the authentic teaching of the Council in educating her own members and in evangelising the world. As well, the format of the Council documents was diffuse, rather like extensive essays; they were such a contrast to the brief, clear, synthetic canons of previous general councils and they left its teaching open to distortion and misinterpretation. Many Catholics, and perhaps a majority of priests, have thus been convinced that the Council committed the Church to programs of liberalism and social action.

Archbishop Bugnini

I was present in St Peter’s for the closing of the Vatican Council. With a recently ordained New Zealand priest I had got tickets to be present at the final Mass. Finding ourselves at the rear of the basilica we looked about and noticed the aisle behind the bishops’ stalls; there was nobody there so we moved cautiously forward. We were making good progress when suddenly around a corner swept the Secretary of the Council, Archbishop Pericle Felici, resplendent in cope and mitre flanked by two Swiss Guards carrying halberds and moving swiftly towards us. We turned tail and fled. At one point I looked back and the three of them were all laughing. So, discomfited, we took our lowly place at the back of the basilica.

When the Council ended Rome seemed like a deserted city. This was a better atmosphere for study so I finished my dissertation and defended it to the satisfaction of Father Hamer and a board of Dominicans. Before leaving for Christchurch in 1966 to be a parish priest for ever, which was what I wanted, I decided to call on Monsignor Bugnini to see if he could give a relatively young priest any good practical advice about beginning to carry out what the Council had asked for. After shepherding the Constitution on the Liturgy through the Council, he had become Secretary of the Consilium responsible for implementing the Councils’ recipes for reshaping the liturgy. He received me graciously , full of good humour. In response to my request he told me this parable:

‘You Anglo Saxons,’ he said, ‘when you are driving and you come to a green light you go on, cautiously. When you come to an amber light you brake and begin immediately to stop. When the light turns red you stay completely still. Then when it turns green you look around carefully and finally get going again.

‘In Italy, it is different. We Italians see a green light and keep right on going. If it turns amber we glance at it and keep right on going. If it is already red we look around and if there are no cars coming and we see no traffic cop we keep right on going.

‘To make the most of all the new liturgical possibilities given by the Council you must become like Italian drivers.’

So with laughter and bonhomie we parted. As life went on I could see how irresponsible Mgr Bugnini’s advice had been. Finally Pope Paul VI got wind of his lawless tendencies, though too late to forestall all the damage he had done to the Church’s liturgy, and Bugnini lost his powerful position in Rome; he ended up as nuncio in Iran. I believe he was never asked by the Muslims to help reshape their form of worship.

The Pontifical Council for promoting Christian Unity

Perhaps this should be the end of my talk but it was not the end of Rome for me; in fact it was the beginning of coming to terms very closely with what the Council had decided in one particular area. When I had gone off to my parish in New Zealand, Father Hamer had become Secretary of the Council for Promoting Christian Unity. Then when one of the desks in that office became vacant (the religious who occupied it had been elected general of his congregation), Father Hamer put my name forward and I was invited to join the staff. Having just begun to settle down in a parish after the first Roman experience which had been so stimulating an experience, I hesitated to be uprooted again. However the bishop of the time, who may have felt I was following the Bugnini line too closely, persuaded me to go back to Rome for just two years, he said, which is what I did in 1969. It was 1987 before I got back to live again in Christchurch. Meanwhile I had a ringside seat for seeing the implementation of the Decree on Ecumenism, Unitatis Redintegratio, an experience which confirmed some of my previous ideas about ecumenism and challenged others. It was also a good place from which to see something of what was happening in the Church to the teaching of Vatican II.

The Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity had begun as an ad hoc body to prepare for Vatican II and to shepherd the draft of the Decree on Ecumenism through the Council; it was erected as a permanent dicastery of the Roman Curia towards the end of the Council since clearly there had to be some organ staffed by people prepared for the task, to work out the implications of the Decree and to monitor its implementation throughout the Church. In the Curia at that point there was a clear differentiation — almost, one might say, a class distinction — between the old offices which had an executive function and the new ones that came from the Council and were for promotion and study of certain themes. However, it had been said in the Council that the Decree on Ecumenism had to be interpreted in light of Lumen Gentium (the Constitution on the Church), so the Pontifical Council for Unity had an immediate link with the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith and one which became closer as time went on. Though it was not always a comfortable fit it gave the Pontifical Council a certain clout in the Curia and kept it before the attention of the pope.

During his pontificate, Pope Paul VI’s attitude to the office was ambiguous; sometimes we would get his approval, other times we were out in the cold and this latter attitude became more marked as his pontificate drew to a close. When John Paul II was elected we wondered if this Pope from Poland would know much about our work. About three months later an acquaintance from the Secretariat of State whom I met in the street one day said; “Doesn’t this new Pope know there is any other dicastery in the Curia than your office?” and, in displeasure, he marched on, leaving me reassured. Indeed Pope John Paul II used our services fully. So I got to know him from occasional audiences to deal with certain ecumenical questions and occasions and a few times from being at meals with him.

Then Cardinal Ratzinger had a watching brief over much of our work; the more progressive among us rather feared him. I found him always gracious and helpful, often meeting him in the morning as we were going to work in opposite directions across St Pater’s Square. In practice our office was also very ready to cooperate with other dicasteries, whether old or new; thus I had quite close working relations with the Congregation for the Evangelisation of Peoples and with the Pontifical Councils for Justice and Peace, for the Laity and with Cor Unum.

Plenary Assemblies

When I had arrived there in 1969, the Dutch Cardinal, Jan Willebrands, was the president of the Pontifical Council and there were nine staff members. Willebrands had been a philosopher and the strategy of the office was worked out with considerable acumen. As a result it was well under way while some of the other post-conciliar dicasteries were still trying to find their place. We were fortunate in having some strong cardinals and bishops appointed as members and full use was made of an annual plenary assembly of members to plan policy and action. At first coming newly to it, I was a bit surprised at how hesitant some of the members seemed about ecumenism. However because a good atmosphere prevailed in the plenary and because the staff were both capable and friendly, a certain team spirit emerged.

As well, numbers of the members were well prepared for the role. One such was the Bishop of Bruges who acted as vice-president though not resident in Rome. Msgr Emil de Smedt — known familiarly as BBB, from the sources of his family wealth: Brewer, Banker, Bishop — had played a significant role during the Council on the progressive wing in the debates. In the plenary assembly of our office he chaired the sessions with great aplomb, conducting them in Latin. Staff projects that he backed tended to go ahead with the full acceptance of the bishop members.

Some memories from the plenary assemblies will always remain. Around 1980 when there was a lot of pressure from feminists in the Church for the ordination of women, at one plenary Cardinal Hume, without warning, asked Cardinal Willebrands the question: “Do you think it could ever be possible for the Catholic Church to ordain women?” There was a shocked silence. Then after a pause Willebrands looked up and said “I do not see how it is possible.” He then went on to give a clear statement of the reasons. But Hume had tried.

At a later plenary around the turn of the century, when Cardinal Walter Kasper had become president of the Pontifical Council, and with Cardinal Ratzinger present ex officio as usual, a discussion developed between the two cardinals on what Kasper had said in his opening address. It was a question of whether or not the Catholic Church from its inception in Jerusalem, is a universal Church or whether it began as the local church of Jerusalem which incrementally became a universal church. This was a continuing public argument between the two German Cardinals. Kasper made his case with a certain heat. Ratzinger looked at his former pupil with a calm smile, analysed Kasper’s case and demonstrated that the Church founded by Christ and the Holy Spirit in Jerusalem was from the outset the universal Church. It was high theological entertainment.

Life in the Curia

Being an official of the Pontifical Council was a bureaucratic job — meetings, reports, study; certainly a long way from being a parish priest. However among the staff there were those who did not travel if they could help it, and there were those ready at any time to go anywhere. I was among the latter. Since we were a small number our responsibilities were on several levels. The international theological dialogues held first place; then institutions with which the Catholic Church had contacts such as the Lutheran World Federation, the World YMCA, and many others; then questions that needed to be researched; and finally the regional desks. Since the staff at that time was still composed of people from Europe or the USA, for a time I ended up with the regional desks for English-speaking Africa, Asia, the Caribbean and the Pacific. Because I had also the WCC desk I went to Geneva on an average of once a month. My travel was far flung and regular, which meant my job was not a typical Curial one which would have had me stuck at a desk in Rome for 11 months of the year. It also meant a lot of human contacts. In the office there was a good working atmosphere among the staff including the secretaries who were women from several of the new ecclesial communities. Each morning we had a coffee break at 11.00 when the staff and any visitors to the office would gather.

From 1978 until 1983 when Cardinal Willebrands was Primate of Holland as well as our president, Bishop Ramon Torrella, a Catalan who had stood up to Franco and had been given refuge in the Curia, was our resident vice-president. He was a friendly, humane man who in his apartment liked to cook spaghetti alla carbonara for friends. (Incidentally, the knack is to have the right temperature when mixing the cheese and eggs for the sauce.) On special occasions or feast days, at the coffee break he would produce a couple of bottles of La Ina, the top quality fino from Domeq, the Spanish sherry producer. Since Msgr Torrella, a couple of Englishmen and myself were the only ones who had a taste for sherry, on those days one would get back to one’s office in a pleasant haze and do gentle jobs until we broke for lunch at 1:30.

The Ecumenical Directory

Apart from occasionally drinking sherry, what did we do? A major project in the very first years had been the preparation of a brief ecumenical directory that would enable the implementation of the more theoretical Decree on Ecumenism of Vatican II. By 1985 there had been so many developments, some good, many less good, that more needed to be said about Catholic principles on ecumenism and many more practical guidelines given for ecumenical action. I was the staff member appointed to work on a draft for a new and fuller directory with one of our consultors, the dean of the canon law faculty at the Pontifical Salesian University, Professor Tarcisio Bertone.It was a fairly heavy job but Bertone was an excellent canonist and a great person to work with and whenever I have met him since he always remembers that project, probably because it was more successful than some of his more recent ones as Secretary of State. By the time the draft was ready in 1987, I had been sent off to Christchurch as the bishop. However, I had then been appointed a member of the Pontifical Council so I was still involved in the task of getting the draft through our plenary assembly and through the plenary of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith before it went to the Holy Father.

After my departure from the staff, an American Jesuit took over the work on the directory and made it much more permissive. In two plenaries I found my self fighting a rearguard action against Bishop Martensen of Copenhagen (also a Jesuit), Bishop Scheele of Wurzburg, and Bishop Murphy O’Connor (still of Arundel & Brighton). In my arguments I was able to cite the mess I had discovered in my diocese, caused by ill advised and unfaithful ecumenical initiatives. After the document went to the pope it did undergo some changes for the better, but it was finally published in 1993 with what I consider a number of unfortunate loopholes.

The Assisi meeting

Not long before I left the office there had been the Assisi meeting for peace in 1986. Preparation for it was a joint operation involving the Secretariat of State, our office, the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace, and the Pontifical Council for Interreligious Dialogue. Pope John Paul II had the idea and then left it to the rest of us to get on with it. My task was to involve the other Christian churches and eccesial communities on the international level; that meant the Protestants bodies such as the Lutheran World Federation, the Anglican Consultative Council, the world Methodist Conference and so on. It turned out to be difficult. The Protestant ecumenical bureaucrats at first jibbed at engaging in this project along with people from the other world faiths; though personally most of them were rather liberal Protestants they were afraid that their constituents would raise the spectre of syncretism with bad consequences for their budgets. The Orthodox had to be approached directly in each country because of their national organisation, and in the event few of them sent a bishop or any high level representative.

In order to overcome the fears about syncretism the Holy Father had given us the somewhat jesuitical formula: “We shall be together to pray; we shall not pray together.” In fact that is what happened; there was no common prayer involving Christians and other religions. However the distinction was too fine for the journalists; reporting on the event they mostly gave a wrong impression. As a result many Catholics were very upset by the whole initiative, as well as some rotestants. The pope did carry off the whole thing very well despite some stupidity on the part of at least one of the other dicasteries responsible, when they held the prayer for the Buddhists in a church and put a statue of Buddha on the altar. This sort of thing could have been avoided had there been better informed and more sensitive oversight of the whole project.

The Council and the Curia

How did the Roman Curia as a whole view Vatican II and its outcome? For most of the time I was there it was simply not allowable to suggest that what had been done in the Council or even what followed the Council was less than perfect; the Church, despite any evidence to the contrary, was held to be in a much improved situation because of the Council . This was due in part to the influence of a number of influential curial progressives. Of course from the time of his election, Pope John Paul II expressed his full support for what the Council had taught and done while adding carefully: “when it is correctly interpreted,” and he did work strongly for that correct interpretation.

It was only in 1985 with the Extraordinary Synod which gathered presidents of bishops’ conferences to assess the 20 years of the outcome of the Council that it began to be said openly that shadows as well as light have marked that outcome. The report from that Synod, though a very informal document, mentioned specifically some of the shadows. We have been so fortunate to have had Pope Benedict who, with the Year of Faith, has called us to look again at how the Council is to be rightly interpreted and to evaluate what came in its wake. It is a fine touch that his great talk on the Council, given just before his retirement went into effect, both affirms the Council and its necessity and throws further light on misinterpretations and false conclusions drawn from it and which still afflict the Church

Having known Pope John Paul II and worked with him, and having known Pope Benedict before he became Pope and having had an amount to do with him in the CDF, now I do not know Pope Francis at all. So I can only wish him well and pray that, with his fervour and readiness to communicate, he may lead the Church in a fruitful continuity with the teaching of his two immediate predecessors, and with the teaching of Vatican II rightly interpreted.