rubric / “roohbrik” / noun 1 a heading, e.g. in a book or manuscript, written or printed in a distinctive colour or style. 2a a heading under which something is classed, b an authoritative rule, esp a rule for the conduct of church ceremonial, c an explanatory or introductory commentary. rubrical adj. [Middle English rubrike red ochre, heading in red letters or part of a book, via French from Latin rubrica, from rubr-, ruber red]

O worship the LORD in the beauty of holiness! (Ps 96:6)

The past

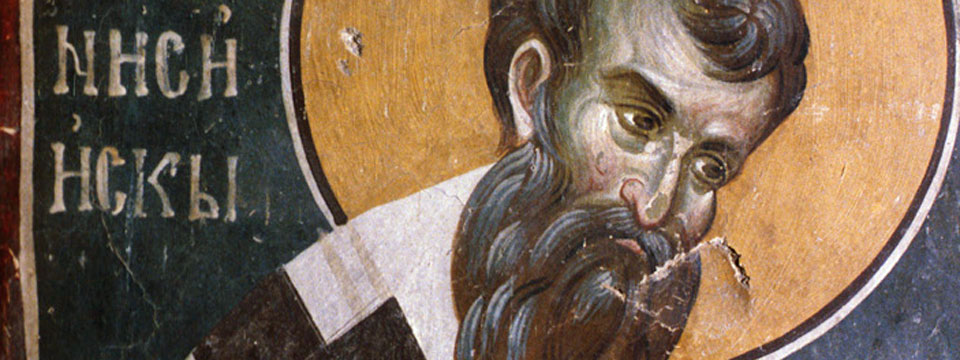

The first-time visitor to churches in Rome’s historic centre is amazed at the richness, indeed the sumptuousness, that he encounters. There are forests of antique marble columns and gold-leafed coffered ceilings; every available space is covered with frescoes, paintings, and mosaics by some of the world’s greatest artists. Even the most ancient and austere basilicas rarely escaped an artistic ‘updating’ during the baroque or rococo periods. The heavily-decorated ambience leads some to recall an axiom that seems at work here: magis melior est ‘more is better’.

To a greater or lesser degree, many old churches across Europe were likewise bedecked with the local architectural and artistic specialties: spires, flying buttresses, stained glass, ornate gilt wood carvings, and a treasure-trove of artworks. Catholic emigrants from Europe brought this philosophy to their new homes around the world. It is truly amazing how these people, usually struggling to build homes and eke out a living, managed to build some of the churches and chapels that are now visited by tourists who gaze in awe at what they see.

To match the splendour of the surroundings, liturgical vestments were also splendid. Chasubles and copes heavy with gold embroidery, albs and surplices decorated with the finest lace: these were often the product of hundreds of hours of handiwork by cloistered nuns or dedicated peasant women. They were given as votive offerings to enhance the worship of God, and carefully stored between layers of tissue paper in sacristy drawers. And this rich apparel was not only found in great city churches; many country parishes prided themselves on their ‘feastday’ vestments.

Parishioners were happy to contribute generously toward the needs of worship. There were three important motivations: a sincere belief in what was being celebrated, the conviction that ‘God deserves the best’, and a certain satisfaction in being able to memorialise loved ones, living and dead, through their donations.

Then ‘the spirit of Vatican II blew into the open windows of many, if not most, parishes. The belief that reunion with our’ separated brethren’ was imminent was one of the factors that influenced Catholic liturgical renewal. Awelcome focus on Scripture, seen not only in the revised lectionary but also in newly-invented ‘bible vigils’ and in new hymn texts, was a none-too-subtle reminder to Protestants that ‘we, too, are Bible people’. Unfortunately, it seemed to many ‘liturgists’ that other things had to go in order to make room for the Bible, including Eucharistic and Marian devotions.

Churches needed to be simplified, too. The new ideal was ‘less is better’. Old churches were ‘renovated’, which in some cases meant ‘vandalised’: statues were removed, frescoes white-washed, marble flooring covered with carpeting. Felt and burlap banners, potted plants, and children’s artwork taped to the walls adorned the new liturgical ‘environment’.

Vestments kept up with the new trend. Polyester replaced linen, wool and silk; gold-embroidered chasubles and copes were mothballed (or, worse, tossed out or cut up to make banners) and the children made stoles for Father that were embellished with everything from animal cutouts to characters from comic strips.

The present

Fortunately, the worst of 20th century iconoclasm seems to be behind us, and attempts are being made to bring us back to the ‘liturgical middle’: a happy medium between flamboyant baroque and sterile post-modernism. People don’t want their churches to look like bank lobbies; they want them to look like … well, churches! And they want their churches to be beautiful.

For great is the LORD and highly to be praised…

Splendour and power go before Him;

power and grandeur are in His holy place …

O worship the LORD in the beauty of holiness! (Ps 96:4a,6)

The ‘new and improved liturgical movement’ is sometimes disparagingly called ‘the restoration movement’. There’s nothing wrong with that title, because there truly is a movement afoot to restore perfectly valid and good parts of our spiritual tradition that were discarded a bit too enthusiastically: Gregorian chant, Eucharistic and Marian devotions, the Extraordinary Form of the Mass, and classical styles of church architecture, among other things.

Beautiful vestments are among those ‘other things’. True, beauty is in the eyes of the beholder, but it’s fairly easy to see now that some liturgical fashions simply don’t make the grade. If you aren’t convinced, then attend a Mass during which a large number of concelebrating priests bring their own vestments.

Check out the albs: there will be some that look really good. But others have been ‘washed and worn’ one too many times. The Velcro tabs on their collars and built-in cinctures aren’t holding well anymore, so Father’s sport shirt is visible beyond the open collar and the cincture is flapping around uselessly. And that’s not all: the necklines are discoloured with dirt, and the hemline is somewhere between the shin and kneecap.

Check out the stoles: again, some will be worthy of admiration. Others will be best consigned to the liturgical ‘Believe It or Not’ museum: the appliques range from Sixties peace symbols and Seventies balloons to Eighties rainbows and Nineties recycling symbols, depending on when the good Father was ordained.

We won’t check out the chasubles, because (a) many priests don’t bother with them anymore, (b) or, if they do, they match the stoles enough said, or (c) if a matching set of chasubles is available, they are usually trimmed with a silk-screened strip of crosses. Enough said.

The reform of the reform

Pope Benedict XVI has been making a silent statement with his choice of vestments; there are those who like it, and those who don’t. It is not the purpose of this article to discuss papal attire, but it is relevant to examine what the Holy Father is saying by his choice of liturgical vesture.

As is well known by now, the Pope supports a ‘hermeneutic of continuity.’ He believes and rightly so that to draw a line in the sand between a pre-Vatican II and post-Vatican II Church is wrong. The Council never said that any liturgical practices should be rejected, but rather that they be renewed. Because the Council permitted options to Latin and the position of the priest at the altar did not mean that the Council forbade Latin or Mass ad orientem. But we know what happened.

Now the Church is asking for the recovery of a sense of beauty in the liturgy. The General Instruction of the Roman Missal (GIRM) gives this instruction:

22. The celebration of the Eucharist in a particular Church is of utmost importance…. The Bishop should therefore be … vigilant that the dignity of these celebrations be enhanced. In promoting this dignity, the beauty of the sacred place, of music, and of art should contribute as greatly as possible.

Vestments should be works of art. (If you disagree with that premise, talk to a good seamstress or tailor.) They should enhance the beauty of a celebration, not only by their colour, but by the way they drape the ministers and add to the majesty of a procession or the solemnity of a ‘Let us pray’. There is absolutely nothing wrong with having a vestment that is precious; even Jesus owned a garment that was considered ‘above the ordinary cut’:

When the soldiers had crucified Jesus, they took His clothes and? divided them into four shares, a share for each soldier. They also took His tunic, but the tunic was seamless, woven in one piece from the top down. So they said to one another, ‘Let’s not tear it, but cast lots for it to see whose it will be.” (Jn 19:231)

And vestments are sacred. In the ‘pre-Conciliar Church’, vestments were always blessed before their first use. Prayers were said as the ministers prepared to put them on, and as they did so, they kissed the crosses embroidered on them. When taken off, vestments were not tossed onto a shelf or crammed into a over-stuffed wardrobe, but properly stored away. There were linen collars on stoles that could be removed and washed, thus avoiding that ‘ring around the collar’ look. And when vestments became worn, they were sent to convents or repair shops for restoration.

Sacred vestments and Sacred Scripture

This sense that vestments are sacred, that they should be beautiful, and that they should add majesty to a celebration is not an invention of the Council of Trent. It comes to us from the Bible:

The Lord clothed (Aaron) with splendid apparel and adorned him with the glorious sacred vestments… majestic, glorious, renowned for splendour, a delight to the eyes, beauty supreme. Before him, no one was adorned with these, nor may they ever be worn by any except his sons and them alone, generation after generation, for all time. (Si [Eccles] 45:8a, 10a, 12b-13)

The greatest among his brethren, the glory of his people, was Simon the priest, son of Jochanan … How splendid was he … as he came out of the tent… vested in his magnificent robes and wearing his garments of splendour, as he ascended the glorious altar and lent majesty to the court of the sanctuary. (Si [Eccles] 50:1,5,11)

The Church supports this biblical concept, and reminds us that beautiful things can more aptly remind us of the beauty of heaven. The GIRM states:

288. For the celebration of the Eucharist, the People of God normally are gathered together in a church or, if there is no church or if it is too small, then in another respectable place that is nonetheless worthy of so great a mystery. Churches, therefore, and other places should be suitable for carrying out the sacred action and for ensuring the active participation of the faithful. Sacred buildings and requisites for divine worship should, moreover, be truly worthy and beautiful and be signs and symbols of heavenly realities.{{1}} [[1]](Cf, Second Vatican Ecumenical Council, Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy, Sacrosanctum Concilium, nos. 122-124; Decree on the Ministry and Life of Priests, Presbyterorum ordinis, no. 5; Sacred Congregation of Rites, Instruction Inter Oecumenici, On the orderly carrying out of the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy, 26 September 1964, no. 90: AAS 56 (1964), p. 897; Sacred Congregation of Rites, Instruction Eucharisticum mysterium, On the worship of the Eucharist, 25 May 1967, no. 24: AAS 59 (1967), p. 554; Codex Iuris Canonici, can. 932 § 1)[[1]]

Vestments are one of the ways in which the Church imitates and anticipates worship in the heavenly Jerusalem:

After this I had a vision of a great multitude, which no one could count, from every nation, race, people and tongue. They stood before the throne and before the Lamb, wearing white robes and holding palm branches in their hands. (Rev 7:9)

Vestments transcend the changing fashions of the centuries, and become symbols of Christian realities. For example, the ministers at the altar who wear white albs are reminding us that the liturgy proclaims Christ crucified and risen:

On entering the tomb, [the women] saw ayoung man sitting on the right side, clothed in a white robe, and they were utterly amazed. He said to them, ‘Do not be amazed! You seek Jesus of Nazareth, the crucified He has been raised; He is not here. Behold the place where they laid Him.’ (Mk 16:5f)

The deacon, priest and bishop, clothed in their white Easter baptismal garments, also wear stoles, for they are leading us into the sacred mysteries that promise eternal life:

After this I had another vision. The temple that is the heavenly tent of testimony opened, and the seven angels … came out of the temple. They were dressed in clean white linen, with a gold sash around their chests. (Rev 15:5f)

The celebrant who does not omit his Eucharistic chasuble (for the stole, while common to all sacramental celebrations, is not of itself a Eucharistic vestment) draws the entire assembly into Christ’s embrace as he extends his arms in prayer:

And over all these [other virtues] put on love, which binds the rest together and makes them perfect. (Col 3:14)

The chasuble has no connections with Temple worship, but is descended from the Roman travelling garment or overcoat, the casula. As such, it is a reminder that we are (as Vatican II stated) a ‘pilgrim people’, a concept that is rich in biblical foundation. In the early Church, the chasuble was considered so essential to the Eucharistic celebration that even the acolytes wore it. For a celebrant to omit wearing it today is not in harmony with the connection between the Eucharist and the Passover:

The LORD said to Moses and Aaron in the land of Egypt: ‘This is how you are to eat it: you shall eat like those who are inflight. It is the Passover of the LORD. ‘ (Ex 12:1,11)

In short, vestments are not just ‘robes’. They are rich in scriptural and liturgical meaning, and so they should be rich in fabric and design as well. They are, if you will, the ‘court dress’ of those who serve a true King:

The LORD is king, robed with majesty; the LORD is robed, girded with might. (Ps 93:1)

The rubrics relating to vestments

The last part of this article will examine Chapter V, Part IV of the GIRM, which deals specifically with vestments. The salient points in each article are highlighted, and some comments follow.

335. In the Church, which is the Body of Christ, not all members have the same office. This variety of offices in the celebration of the Eucharist is shown outwardly by the diversity of sacred vestments, which should therefore be a sign of the office proper to each minister. At the same time, however, the sacred vestments should also contribute to the beauty of the sacred action itself.

It is appropriate that the vestments to be worn by priests and deacons, as well as those garments to be worn by lay ministers, be blessed according to the rite described in the Roman Ritual before they are put into liturgical use.

The prayers for the blessing of vestments are found in n. 1070 of The Book of Blessings:

336. The sacred garment common to ordained and instituted ministers of any rank is the alb, to be tied at the waist with a cincture unless it is made so as to fit even without such. Before the alb is put on, should this not completely cover the ordinary clothing at the neck, an amice should be put on. The alb may not be replaced by a surplice, not even over a soutane, on occasions when a chasuble or dalmatic is to be worn or when, according to the norms, only a stole is worn without a chasuble or dalmatic.

There have been several directives reminding members of religious institutes that the religious habit does not replace the alb, even if the habit is white. The habit, like the soutane, is not a liturgical garment. In places like Rome, where one commonly sees the soutane or habit worn as street dress, one would never expect to see a priest walking down the street in an alb. Simply because some communities have relegated the habit to occasional use does not allow its substitution for the alb:

337. The vestment proper to thepriest celebrant at Mass and other sacred actions directly connected with Mass is, unless otherwise indicated, the chasuble, worn over the alb and stole.

Thus the wearing of the stole over the chasuble is irregular. True, some recently-designed stoles are intended to be worn over the chasuble. However, this has led some priests to wear any stole over any chasuble, resulting in stoles obscuring the symbols on chasubles that are obviously meant to be worn over the stoles.

338. The vestment proper to the deacon is the dalmatic, worn over the alb and stole. The dalmatic may, however, be omitted out of necessity or on account of a lesser degree of solemnity.

Note: ‘heat’is not an excuse for omitting vestments. For centuries, missionaries in the tropics wore complete sets of vestments over woolen soutanes (until ‘the spirit of Vatican II’ dictated otherwise), and there have been no recorded martyrdoms from sweating to death during Mass!

339. Acolytes, lectors, and other lay ministers may wear the alb or other suitable vesture that is lawfully approved by the Conference of Bishops (cf no. 390).

Quite a few European and American parishes have found that clothing all liturgical ministers in the alb or a garment similar to a ‘choir robe’ not only adds beauty to the celebration, but obviates the growing problem of ministers who are inappropriately attired.

340. The stole is worn by the priest around his neck and hanging down in front. It is worn by the deacon over his left shoulder and drawn diagonally across the chest to the right side, where it is fastened.

341. The cope is worn by the priest in processions and other sacred actions, in keeping with the rubrics proper to each rite.

342. Regarding the design of sacred vestments, Conferences of Bishops may determine and propose to the Apostolic See adaptations that correspond to the needs and the usages of their regions.

In the Western world, the only such adaptation proposed to and approved by the Holy See has been the so-called ‘chasualb’. Its very limited use, usually restricted to priests of a limited vintage, indicates that it has corresponded neither to our needs nor our usages.

343. In addition to the traditional materials, natural fabrics to each region may be used for making sacred vestments; artificial fabrics that are in keeping with the dignity of the sacred action and the person wearing them may also be used. The Conference of Bishops will be the judge in this matter.

While permitted, the ubiquitous use of synthetic materials has made vestments more uncomfortable to wear in warm climates. Consider the priest who wears a T-shirt, (clerical) shirt, alb, and chasuble. The polyester chasuble and polyester/cotton alb he is wearing traps the heat inside, and his shirt and T-shirt become wringing wet with sweat. Linen, wool and silk are natural fabrics that ‘breathe’, which is why older vestments made from those materials have sometimes lasted for centuries. ‘The Conference of Bishops will be the judge in this matter’, but common sense should be factored in.

344. It is fitting that the beauty and nobility of each vestment derive not from abundance of overly lavish ornamentation, but rather from the material that is used and from the design. Ornamentation on vestments should, moreover, consist of figures, that is, of images or symbols, that evoke sacred use, avoiding thereby anything unbecoming.

The ornamentation of some contemporary vestments betrays poor artistry, mass-produced by companies that have not been gifted with a ‘good taste’ gene. However, consideration should also be given to the fact that some symbols, no matter how well executed, do not make liturgical sense. Example: if the church uses a real Advent wreath, why wear a chasuble depicting an Advent wreath? Worse, just because the Advent wreath chasuble is purple doesn’t justify wearing it during Lent! Likewise, a purple chasuble decorated with a crown of thorns and three nails is obviously meant to be used during Lent, not Advent. And when there are lighted candles on the altar, why wear a stole sporting pictures of lighted candles? Symbols ‘evoke sacred use’, that is, they point to realities they don’t replicate the realities they represent. Similarly, it is better to have a wheat-and-grapes design than a host and chalice. Better yet, as the article says: less ornamentation, but finer design and fabric. (And the ‘unbecoming’ comment is probably the Church’s response to Snoopy chasubles and favourite footy team stoles!)

345. The purpose of a variety in the colour of the sacred vestments is to give effective expression even outwardly to the specific character of the mysteries of faith being celebrated and to a sense of Christian life’s passage through the course of the liturgical year.

346. Traditional usage should be retained for the colours of sacred vestments:

a. White is used in the Offices and Masses during the Easter and Christmas seasons; also on Trinity Sunday, celebrations of the Lord (other than of his Passion), of the Blessed Virgin Mary, of the Holy Angels, and of Saints who were not Martyrs; on the Solemnities of All Saints (November 1) and of the Nativity of St John the Baptist (June 24); and on the Feasts of St John the Evangelist (December 27), of the Chair of St Peter (February 22), and of the Conversion of St Paul (January 25).

b. Red is used on Palm Sunday of the Lord’s Passion and on Good Friday, on Pentecost Sunday, on celebrations of the Lord’s Passion, on the ‘birthday ‘feasts of the Apostles and Evangelists, and on celebrations of martyred Saints.

c. Green is used in the Offices and Masses of Ordinary Time.

d. Violet or purple is used in Advent and Lent. It may also be worn in Offices and Masses for the Dead?.

e. Black may be used, where it is the practice, in Masses for the Dead.

f. Rose may be used, where it is the practice, on Gaudete Sunday (the Third Sunday of Advent) and on Laetare Sunday (the Fourth Sunday of Lent).

g. On more solemn days, festive, that is, more precious, sacred vestments may be used, even if not of the colour of the day.

Regarding liturgical colours, moreover, the Conference of Bishops may determine and propose to the Apostolic See adaptations suited to the needs and culture of peoples.

For Funeral Masses, violet may always be used, while black vestments may be used where this is customary. White vestments are also permitted for Funeral Masses in Australia, where this is appropriate.

The GIRM mentions the colour of vestments for funeral liturgies twice, perhaps to rectify the incorrect claims by some that ‘purple and black at funerals went out with Vatican II.’ However, black vestments are actually pretty hard to come by these days, unless a parish either hid them well for about forty years, or purchased new ones.

There has been some criticism of the concept of ‘enforced rejoicing’ at funerals. While we acknowledge Christ’s resurrection, it’s not really good psychology to push people into a denial of their grief, either. The emphasis should be more on ‘hope’ than on ‘joy.’ But civil celebrants have infected us with their idea of ‘the celebration of the life’ of the deceased. After all, their business isn’t about the life of the world to come, so they have no alternative but to look back to the life that was. However, Christian funerals are not simply about the past, and should be different. There is a revision of the funeral rites being planned. While maintaining the option of white for the funeral Eucharist, it will encourage more strongly the use of purple or black for the vigil and committal services, in order to be in tune with the solemnity and grief that usually attend the viewing of the body and the farewell at the cemetery.

Note the comment in (g). The best vestments should be used for the greatest festivals of the Church. There is nothing wrong with wearing a magnificently embroidered Roman or Gothic chasuble over a simple, unadorned alb; the richness of the fabric and ornamentation will stand out all the better.

347. Ritual Masses are celebrated in their proper colour, in white, or in a festive colour; Masses for Various Needs, on the other hand, are celebrated in the colour proper to the day or the season or in violet if they bear a penitential character. For example, in The Roman Missal, no. 31 (in Time of War or Conflict), no. 33 (in Time of Famine), or no. 38 (for the Forgiveness of Sins); Votive Masses are celebrated in the colour suited to the Mass itself or even in the colour proper to the day or the season.

Votive Masses are underused these days, and would be well-advised for use in schools, since they seem to be forever searching for liturgy ‘themes’. Masses and prayer services that focus on the needs of our troubled world – peace, social justice, relief from poverty, famine or natural disaster, harmony, love of neighbour – will gain added gravitas from the use of purple or red vestments once in a while, rather than the all-purpose white or the ‘ordinary’ green.

For Aaron and his sons there were also woven tunics of brocaded fine linen … the plate of the sacred diadem was made ofpure gold and inscribed as on a seal engraving: ‘Sacred to the LORD.’ (Ex 39:27,30)

Vestments are sacramentals, that is, they are things that derive from the celebration of the sacraments and lead us back to liturgical celebration.

When Jesus and the disciples celebrated the Passover, they wore their prayer shawls. By doing so, they united themselves with all other Jews, past as well as present, to transcend space and time and declare themselves ‘sacred to the Lord’.

Two thousand years after the Last Supper, and some three thousand three hundred years after the Exodus, we continue to gather for the Passover of the Lord. Those who lead us in worship wear clothing that is from another world, because that is what the liturgy is: the meeting of past and future in the present moment, when we leave earthly kronos and enter divine kairos, God’s time that is only ‘now’. Such a timeless moment demands timeless vesture in the sanctuary. For God, only the best will do. After all, God gave only the best for us: His Son. The death and resurrection of Jesus, which we celebrate in our liturgy, is what makes us ‘ sacred to the Lord’. Our vestments remind us of this profound and eternal reality, and assist us in maintaining our liturgical continuum.